Preacher turned peddler: The migration experience of Yūsuf Naṣr/Joseph Nusser

This illustrated article describes one man’s story of relocation from Mount Lebanon to the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was but one among tens of thousands of similar personal experiences in a period of mass emigration from a small part of the Ottoman Empire to the New World but, in telling it, I had the rare advantage of access to an extraordinary collection of documents belonging to and written by Yūsuf Naṣr, aka Joseph Nusser. Many of these have been digitised and are publicly available on the website of the Arab American National Museum (AANM) in Dearborn, Michigan.[1] Many more were kindly shared with me by Joseph Nusser's descendants.[2] The motivations for this family’s migration were primarily sectarian, especially the violent harassment by the Maronite clergy and community in Mount Lebanon resulting from Yūsuf Naṣr’s conversion to the Protestant faith.[3] After briefly sketching out that narrative of persecution, this article aims to focus on the second part of their story, illustrating both the journey undertaken and the life changes required to reinvent a Lebanese individual and family as Americans and, in so doing, represent the larger phenomenon of migration and resettlement in microcosm.

Introduction

Yūsuf Naṣr Muraʾib (c. 1851–1924) was born into a land-owning Maronite Catholic family in the village of Bdādūn, in the hill country about 20 kilometres south-east of Beirut in the Ottoman region of Mount Lebanon. He was employed as a household servant by a wealthy British missionary couple, Mentor and Augusta Mott, who converted him to the Protestant faith. After many years of domestic and community service, Yūsuf Naṣr was accepted by the British Syrian Mission (BSM) as an itinerant preacher and ‘Bible reader’. This formal role, however, antagonised the Maronite clergy and community – among them his own relatives and neighbours – to such an extent that he became the victim of a campaign of ostracism and harassment lasting decades. While his network of supporters expanded to include several foreign missionaries and diplomats, the serial legal problems that resulted from his persecution came to involve Ottoman officials from local level up to the governor himself. Plausibly believing that his life was in danger, Yūsuf Naṣr decided to emigrate to the United States, where he joined the ranks of countless Lebanese immigrants who travelled the roads of New England in the hardscrabble life of an itinerant peddler.

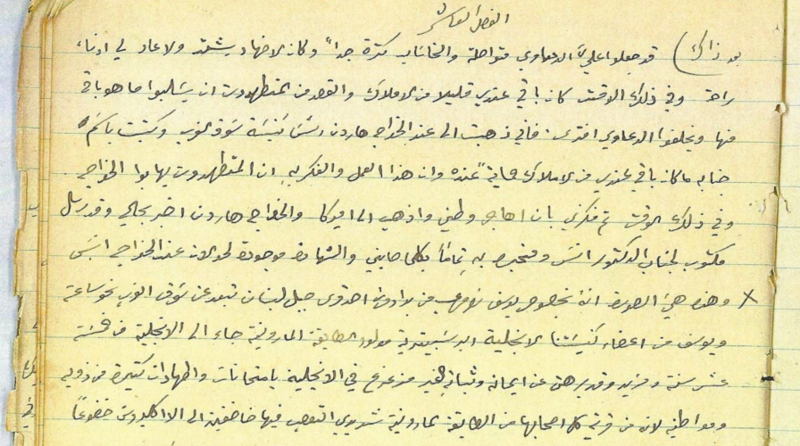

Memoir of Yūsuf Naṣr (detail) © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

This extract from Chapter 10 (f. 13) begins by recalling how an American missionary based at Sūq al-Gharb, Oscar Hardin, wrote to his superiors in the Presbyterian Church to describe the harassment experienced by Yūsuf Naṣr at the hands of the Maronite clergy and corrupt local officials, culminating with the recommendation that Yūsuf Naṣr should migrate to the United States.

The Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate (1861–1918)

A mutasarrifate (Ottoman Turkish: mutasarriflık; Arabic: mutaṣarrifīa) was a quasi-autonomous administrative territory and a unique formulation of the late Ottoman period. The Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon was created in the aftermath of a short but vicious civil war between Maronites and their Druze neighbours, which exploded in the summer of 1860 out of an already simmering sectarian crisis.[4] The violence claimed thousands of lives, with dozens of villages burned and churches destroyed, before spreading to engulf other areas of Muslim-Christian tension and culminating in the slaughter of several thousand people amid the obliteration of the Christian quarter in Damascus.[5] In the aftermath of the killings, the Ottoman imperial authorities demarcated Mount Lebanon as a new political entity similar to that surrounding Jerusalem to the south, a mutasarrifate with statutory protections for Christians in the territory. On 9 June 1861, Sultan Abdülaziz in Istanbul issued a decree (ferman) setting out the skeleton of a Règlement Organique, an ‘organic set of rules’ that formally separated Mount Lebanon from the neighbouring governorates of Beirut and Damascus, further prescribing that the territory’s rulers would be Christians, appointed by and answerable to the central government at Topkapı Palace in Istanbul.[6]

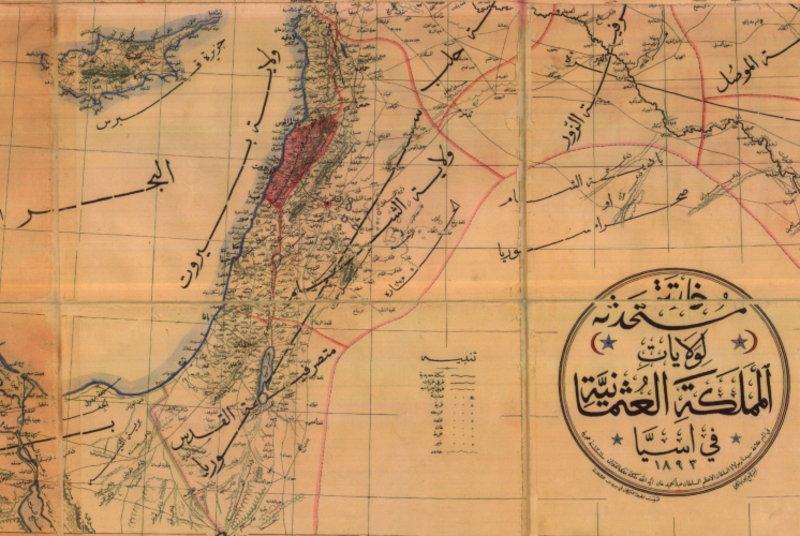

Governorates of the Ottoman Empire (ولايات المملكة العثمانية) (1893). This detail shows the Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon (متصرفية جبل لبنان) coloured in pink, with the separate Governorate of Beirut (ولاية بيروت) on the coast, the Governorate of Damascus (ولاية الشيم) to the east and the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem (متصرفية القدس) to the south. All are clearly demarcated as sub-sections of the larger Ottoman region of Syria (سوريا) Public domain

Protestantism in the Ottoman Empire (1847–1918)

Protestantism was formally recognised as a religious community in its own right (millet) and made legal in the Ottoman Empire on 15 November 1847 – although the administrative decree describing the new regulations governing the Protestant community (Protestan Milleti Nizamnamesi) was formulated not with Lebanese converts in mind but in the specific context of Evangelical Armenians in Istanbul.[7] But two further decrees in November 1850 and June 1853 issued by Sultan Abdülaziz’s predecessor and half-brother, Abdülmecid, had explicitly guaranteed Protestants ‘all the rights and privileges’ of other millets such as Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Armenians and Jews, forbidding their harassment or injury.[8] By the time Protestantism was formally legalised, foreign missionaries had already been active in several parts of the empire for decades. The American Board of Commissionaires for Foreign Missions sent the first Presbyterian evangelists in 1820.[9] The British arrived much later, especially in the Mount Lebanon region.[10] By 1911, an atlas of global missionary activity identified 27 foreign mission societies working in ‘Syria and Palestine’, with another 18 societies scattered across the rest of the ‘Turkish Empire’.[11]

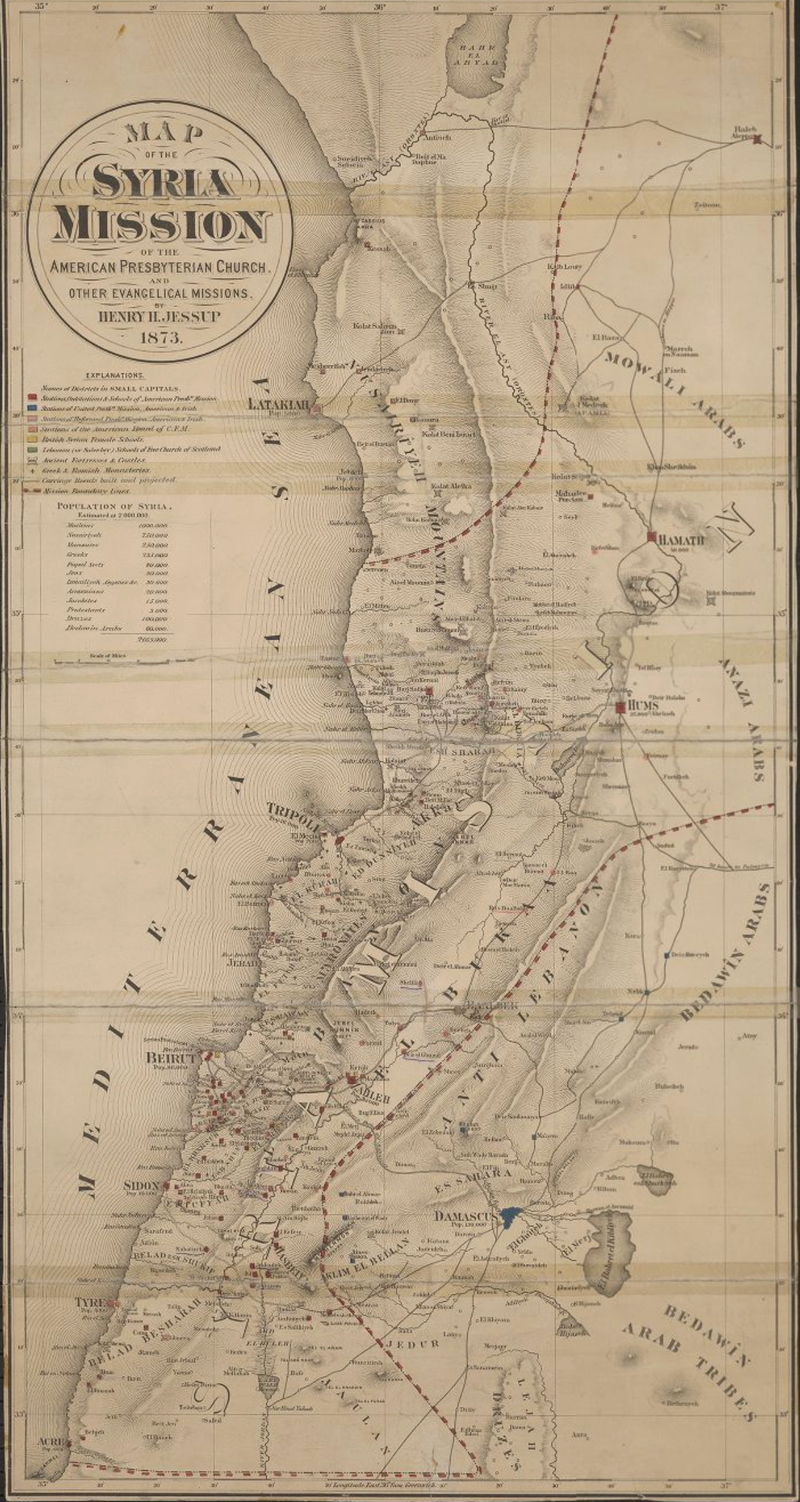

Map of the Syria Mission of the American Presbyterian Church and other evangelical missions, 1873. Source: Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Mapcase 19:15 Public domain

Protestants and Maronites in Mount Lebanon

Despite the relatively small number of conversions such as that undergone by Yūsuf Naṣr, the Maronite clergy, deeply embedded in the rural communities of northern Mount Lebanon, reacted angrily to what they saw as a betrayal of their community. Indeed, by 1864, when Yūsuf Naṣr was in his early teens, one American missionary account described the Protestant community as a ‘small and hated minority’.[12] This anger was rooted in an entrenched mutual antagonism between the foreign missionaries and their local protégés on one hand and the Maronite, Melkite Greek Catholic and Jesuit clergy on the other. Dr James Dennis, an influential American Presbyterian, labelled the Maronites ‘bigoted Papists, very ignorant, and wholly subject to the stringent and ever-watchful control of their clergy.’[13] For their part, Maronite clergymen had been encouraged by their senior hierarchy since the 1820s to burn Bibles distributed by the missionaries, ban all social and commercial interaction and excommunicate converts.[14] Missionary schools regularly complained about harassment by Catholic priests and nuns, ‘anathematising, … carrying off the children, throwing stones and using insulting words to both teachers and pupils.’[15]

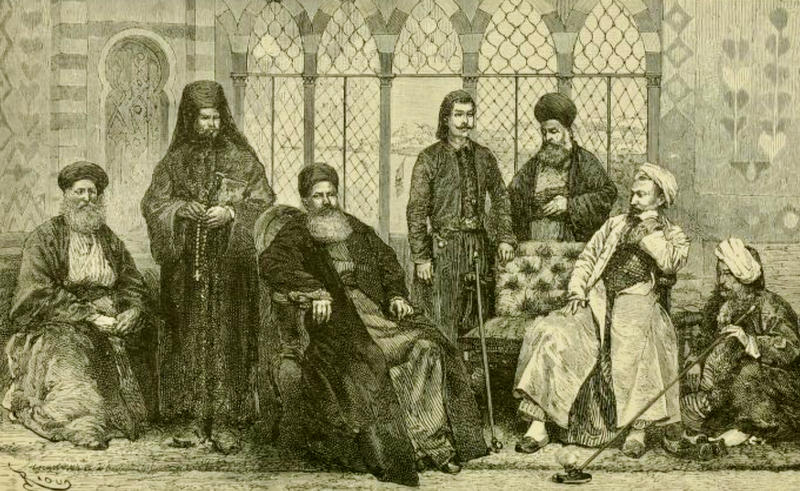

‘Syrian Gentlemen of Various Sects’: taken from William M. Thomson, The Land and the Book or Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land: Lebanon, Damascus and Beyond Jordan (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1886), 84 (facing)

The ostracism of Yūsuf Naṣr

Because of his formal appointment in October 1893 by the BSM as a Bible reader and travelling preacher (mubashir) in and around his home village, Yūsuf Naṣr prompted an intensification of the harassment he was, as a convert, already undergoing at the hands of the Maronite clergy and community.[16] His relationships with both British and American missionary societies were increasingly damaged by a Maronite-led campaign of character assassination and false accusations of financial impropriety. Yūsuf Naṣr was repeatedly forced to solicit testimonials from dignitaries in Beirut and in his own community, who vouched for his good character, honesty in business and integrity as a Protestant role model. But by 1901, he had been subjected to a series of nuisance lawsuits, his family, farm buildings and mulberry orchards had suffered several attacks by his Maronite neighbours, and he had been fired as a preacher by the BSM. Desperate and exhausted, he sought a new life in America.

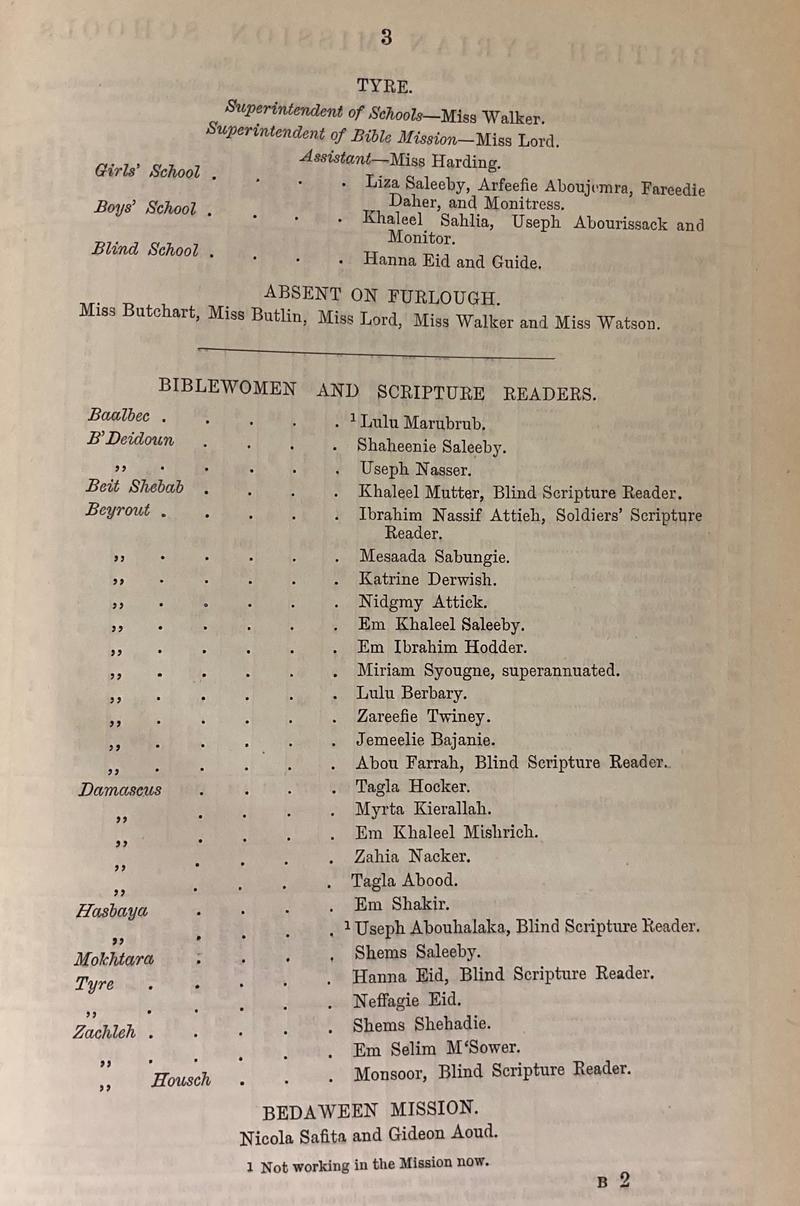

Extract from Daughters of Syria, a monthly update on the work of the British Syrian Mission, October 1893. Source: Middle East Christian Outreach collection, courtesy of the Centre for Muslim-Christian Studies, Oxford

Mass emigration from Mount Lebanon

As a Protestant, Yūsuf Naṣr was among a minority of those seeking to the leave the mutasarrifate: the vast majority of the tens of thousands who emigrated during this period were Maronites.[17] Contemporary French diplomatic correspondence gives us a vivid picture of this phenomenon. In April 1890, the French Consul-General to Beirut reported back to Paris that he had witnessed as many as a hundred men, women and children from a single Maronite village, preparing to embark for a new life in Argentina to escape ‘poverty and official abuses’.[18] French, Italian, British and Greek merchant fleets vied for the lucrative two-stage business of transporting Lebanese migrants: first to Europe and then on to the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Australia. The Marseille-based Messageries Maritimes, for example, exemplified the pragmatism of European shipping companies in pursuing commercial success by ignoring episodic bans on emigration, bribing port officials where necessary and making clandestine midnight collections of passengers away from the bright lights of Beirut Port itself.[19]

1901 map showing routes operated by the Marseille-based company Messageries Maritimes in the Mediterranean (including Beirut) and the Bosphorus. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1997 002 5205 Public domain

Yūsuf Naṣr’s family (c. 1885–1900)

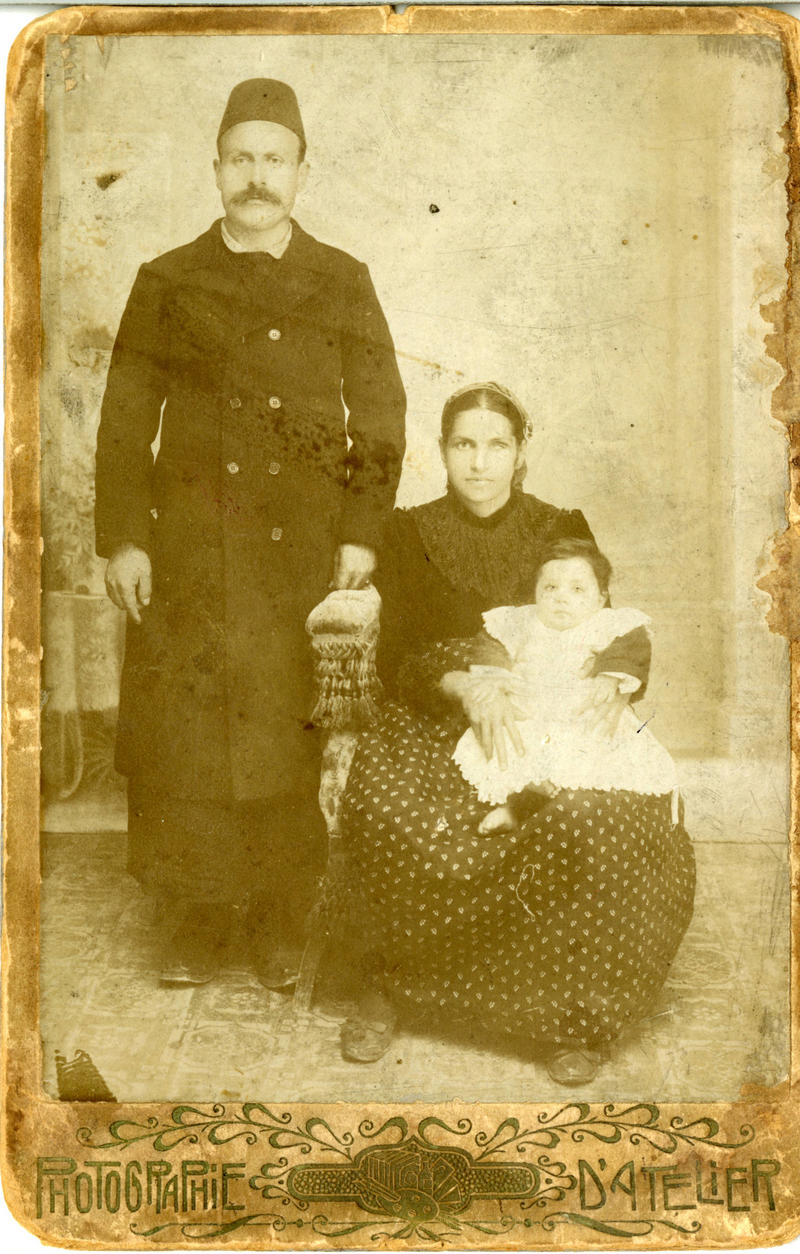

Because Yūsuf Naṣr’s memoir is devoted exclusively to his grievances against the Maronite hierarchy and their accomplices, he scarcely mentions his family. But by 1900, Yūsuf – now in his late forties – had been married for at least 15 years to Tabtī Yūnis Shalūb, a local woman who was blind in the left eye. Following the recent discovery of a notebook in which Yūsuf Naṣr recorded the dates of all his children’s births and (up to the time of writing) deaths, we know that, on the eve of his departure for America, the couple had five sons and one daughter, whose ages ranged between 13 and two: Ilyās, Naṣrī (later known as Yūsuf Jr.), Tawfīq, Najīb, Fadwa and Philippe, all living at the family house in Bdādūn. But at the time of Yūsuf Naṣr’s emergency departure from Lebanon, Tabtī was pregnant, so the decision was taken to leave her in Mount Lebanon with the four youngest children and take only the two oldest boys. On arrival in the US, Ilyās would be taken under the wing of Dr. Dennis, the Prebyterian churchman mentioned earlier.[20] Ilyās also received basic training from Dennis’ contacts in the New York silk retail business: Lebanese Protestants with export connections to the Lebanese coast.

Yūsuf Naṣr, his first wife Tabtī Yūnis Shalūb and their last, short-lived child, Anjānī, c. 1901 © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum, Nusser_F17_001a

Yūsuf Naṣr, Ilyās and Naṣrī (Yūsuf Jr.) travel to America (1901)

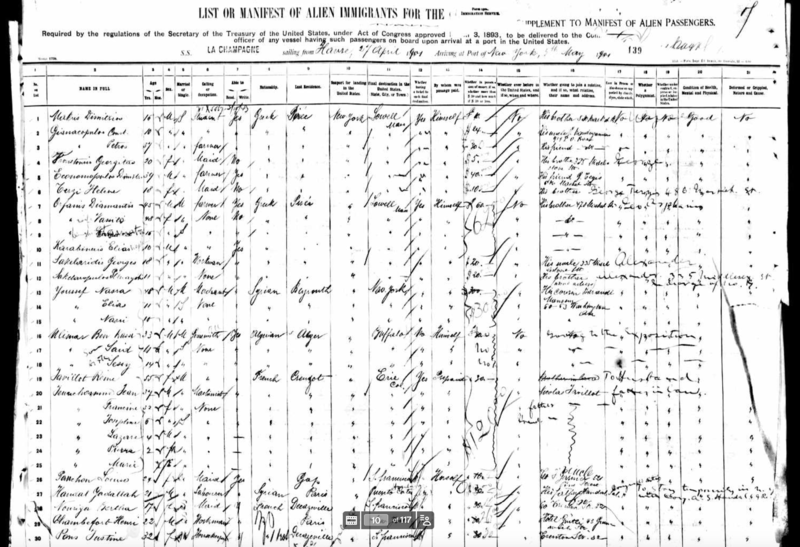

Yūsuf Naṣr’s description of his first journey to the United States is as meagre as his account of his family. There is no detail about his itinerary or accommodation – or how he paid for the three tickets. Nor has the passport, which he and his sons needed to travel outside Mount Lebanon and which might have given us at least a transit destination within the empire, survived. He must have sailed first from Beirut, either directly or via Egypt, to one of the French transatlantic migration hubs, Le Havre or Marseille.[21] The first evidence of their passage can be found in a passenger manifest for the SS La Champagne, a transatlantic liner operated by the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique – also known as French Lines – which left Le Havre on 27 April 1901 and, after a fast crossing, arrived in New York on 5 May.[22] Finding Arab names in such manifests is often difficult: as transcribed by European or American ship’s officers or immigration officials, they were frequently rendered unrecognisable. Here, in the ‘Supplement to Manifest of Alien Passengers’, we find their names written as Nasra Youssef (48), Elias Youssef (11) and Nasri Youssef (10).

The SS La Champagne, owned by the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (French Line), c. 1890–96. Source: Library of Congress LC-D4-22342 Public domain

There are three further details in the manifest worth noting. Yūsuf Naṣr is described as a ‘Merchant’ from Beirut, not a preacher from Mount Lebanon. He is recorded as carrying an impressive $300 in cash, considerably more than any of his fellow passengers and worth around $11,000 in 2024. Finally, the column in the manifest that lists any relative that a passenger might be joining specifies ‘His cousin Baroudi Monsour, 60–63 Washington Ave’. The precise relationship between Yūsuf Naṣr and this ‘cousin’ is unknown but it seems certain that it was an early example of a Protestant support network that not only helped him settle in New York but was also instrumental in getting him started in business. This Mansūr may have been a relative of acquaintances in Mount Lebanon that we know from Yūsuf Naṣr’s memoir and correspondence: Iskandar Bārūdī, a Beirut-based lawyer, and Bashāra Bārūdī, a Protestant preacher just like Yūsuf Naṣr. Assuming that the address on the manifest is an error for Washington Street, Mansūr may have been an employee of Constantine Biskinty, a highly successful Lebanese immigrant and a Protestant, whose commercial address was 60–62 Washington St.[23] Biskinty would later sponsor Ilyās Naṣr’s 1906 application for naturalisation as a US citizen and, in his capacity as a shipping and ticketing agent, may also have arranged Yūsuf’s journey.[24]

Passenger manifest for the SS La Champagne, which sailed from Le Havre in France on 27 April 1901 and arrived at the Port of New York eight days later. Entries 13, 14 and 15: Nasra Youssef (Yūsuf Naṣr), Elias Youssef (Ilyās Naṣr) and Nasri Youssef (aka Yūsuf Naṣr Jr.) © Ellis Island Foundation

Two young Americans (1901–2)

The support network offered by the Lebanese Protestant community in New York continued to help Yūsuf Naṣr during his first forays into the world of the itinerant Syrian door-to-door salesman. It seems likely that he used the contacts provided by Dr. Dennis to procure supplies of silk merchandise in Lebanon that he then had imported to the US. That would explain his description in the passenger manifest as a merchant. Also, he and Ilyās – by now known as Elias and taking his first steps as an independent businessman – were out on the road within a month of their arrival and there are, for the years 1901–2, none of stock receipts from the Washington Street merchants that he would subsequently retain in his files. Naṣrī, meanwhile, his name already Americanised to Yusef Nusser Jr., was left in the care of the Woody Crest charitable boarding school for disabled children in the village of Tarrytown, on the east bank of the Hudson River. The school’s monthly newsletter for November 1901 recorded that Yusef had been sent there by the New York City Missions, while his father ‘hopes to make money enough in a short time to send for the other members of the family.’[25]

Yūsuf Naṣr Jr., photographed at the F. Ahrens studio in Tarrytown, NY, in 1901 © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

‘Yusef Nusser is a Syrian, eleven years old, and could speak but little English when he came to us. He is studying hard every day in school, and is learning rapidly to read and write. He is also able to keep up with his class in arithmetic. His family, like many others in Syria, have suffered persecution and imprisonment. His father, a brother fourteen years old, and he, under a guard of soldiers fled to the Mediterranean coast, and escaped to America last June.’ (Woody Crest Monthly, November 1901, pp. 1–2)

The reluctant door-to-door salesman (1901–2)

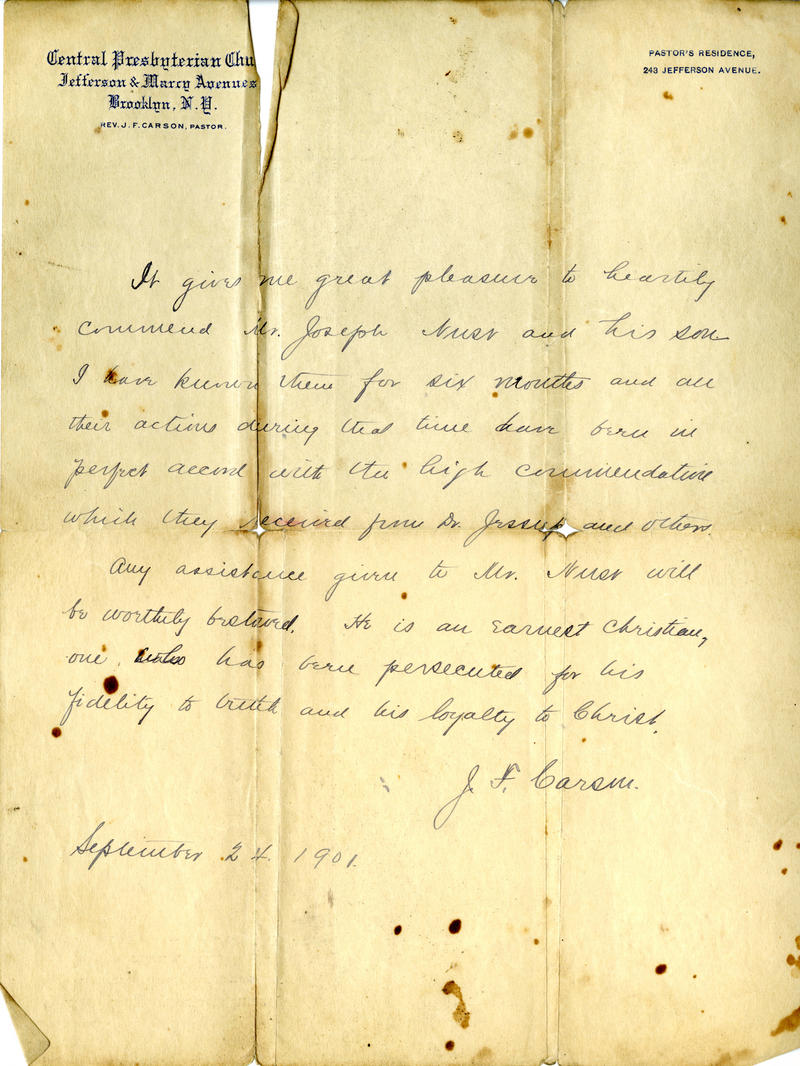

Yūsuf Naṣr travelled through upstate New York during the summer of 1901, presumably from a base in the Lower West Side of Manhattan, where the recent influx of Lebanese had created what their American neighbours called Little Syria.[26] To buttress the character references he had brought from Lebanon, he secured letter of endorsement from two influential New York Protestant figures: Frederick B. Richards of the 14th Street Presbyterian Church in Manhattan on 26 May 1901 and John F. Carson of the Central Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn on 24 September 1901.[27] He also obtained references from satisfied customers, such as Dana Bigelow of Ithaca, NY, who noted on 10 July: ‘The bearer of this note is from Syria, is well endorsed as worthy by Dr. Dennis of the Presbyterian Board. He has handsome hand made work, for sale at low prices.’[28]

Letter of endorsement from the Rev. John F. Carson of the Central Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

A brief return to Mount Lebanon (1902–5)

Yūsuf Naṣr only stayed in America for eight months. According to the sparse account offered in his memoir, it was the Rev. Carson and his Brooklyn congregation who made possible a return to Mount Lebanon, where he planned to rebuild his life as a preacher, this time working with the US Presbyterian mission. Leaving Elias and Yusef in America, Yūsuf Naṣr sailed for Beirut in early 1902. He returned to Bdādūn to find that his wife Tabtī was terminally ill with cancer and Anjānī, the child she had borne while he was in New York, was gravely ill. Both were dead before the end of September 1902. Because of her marriage to Yūsuf Naṣr, Tabtī died an outcast, denied burial in the Bdādūn cemetery. And when he remarried, seven months later, his second wife, Warda ʿAbdallah al-Badawī from a village near Tripoli, fared little better.

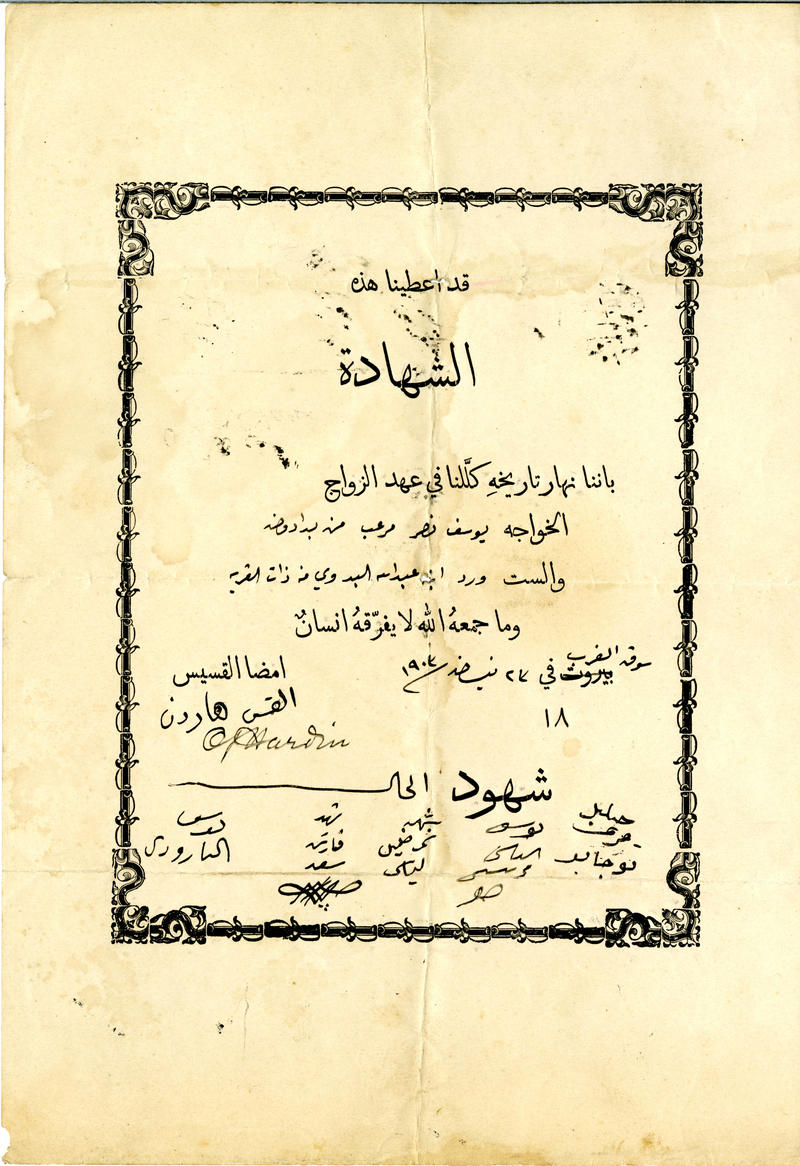

Certificate of Yūsuf Naṣr’s marriage to Warda ʿAbdallah al-Badawī on 23 April 1903, officiated by the Rev. Oscar Hardin, at the church in Sūq al-Gharb © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum, Nusser_F1_001a

Renewed harassment and violence (1902–5)

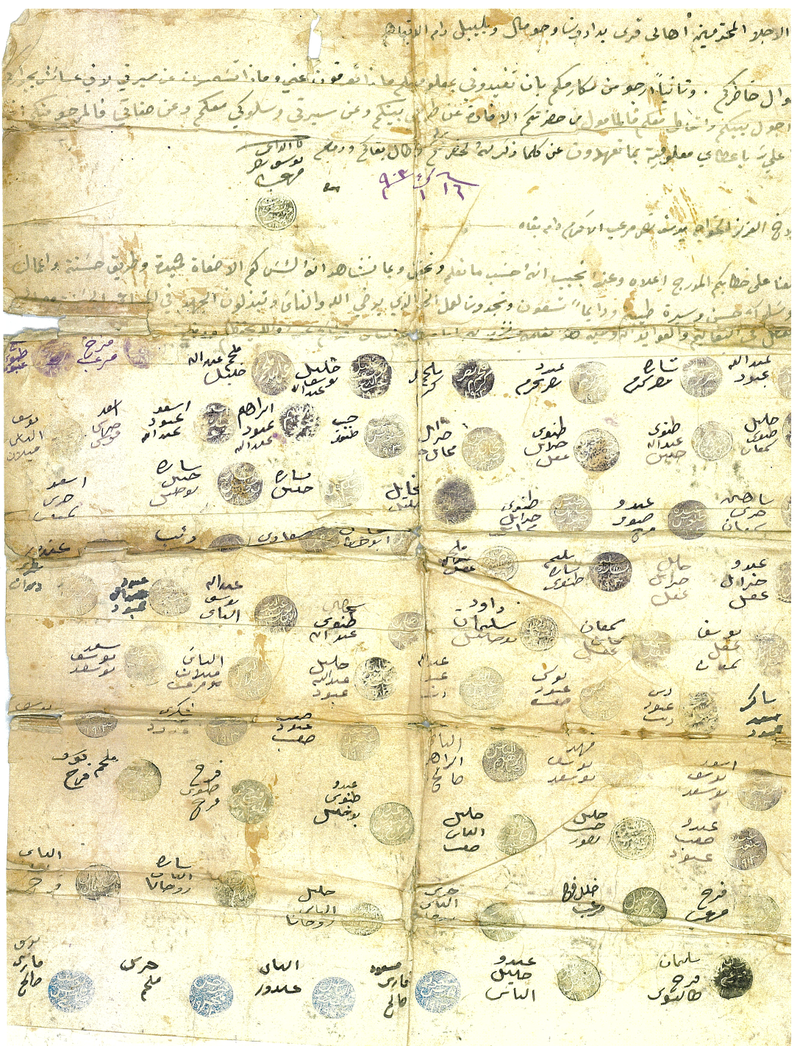

Yūsuf Naṣr’s personal grief was compounded by a new campaign of harassment by his Maronite neighbours. One long sequence of nasty incidents included the overnight demolition of a barn that Yūsuf was rebuilding, the deliberate diversion of a new rural road through his farmland and the brutal beating of his wife and children by a mob of villagers. With senior Maronite clergymen attempting to bribe or browbeat Warda into divorcing him and with the couple’s stubborn resistance leading to their imprisonment, Yūsuf Naṣr again appealed to his community for support. No fewer than 177 neighbours rallied to his defence by signing a letter endorsing his good character – but even this was not enough to save him from being barred from the American church at Sūq al-Gharb on 22 October 1904, with the Rev. Hardin now turning against him too. Again, Yūsuf Naṣr had reached the end of his tether – and when he learned of a plot to kill him in a night-time attack in Beirut, his friends urged him: ‘Save yourself and your family. Go to America and live with your children, because trouble is dogging your steps.’[29]

Response to a petition dated 16 December 1903 from Yūsuf Naṣr asking for a character testimonial from his neighbours, signed and stamped by 177 individual from Bdādūn, Hūmāl and Blībil. Source: Monterastelli Family Collection, B2.2, 3–4.

‘To our dear brother Yūsuf Naṣr, We have read your letter with great interest and are glad to relate all that we have seen and know. You have a good reputation, your character is unblemished, your ways are noble and your deeds are good. You have always worked for the good of others and have pleased both God and man. In fact, you have expended a great deal of energy in doing good. You have at all times the hearty thanks of our grateful people for the holy lessons you have taught them. This is what we know, declared and witnessed before God and man. We are, etc.’

Yūsuf Naṣr, Warda/Rose and the children travel to America (1905–6)

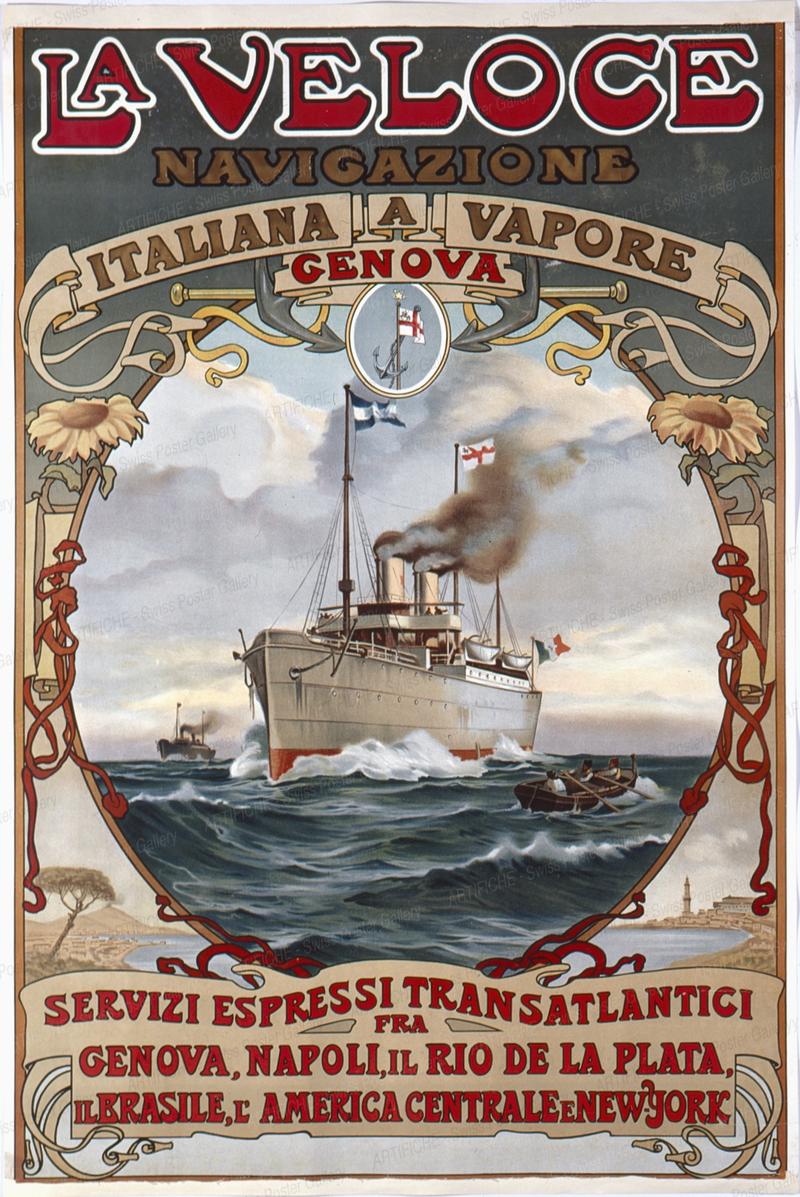

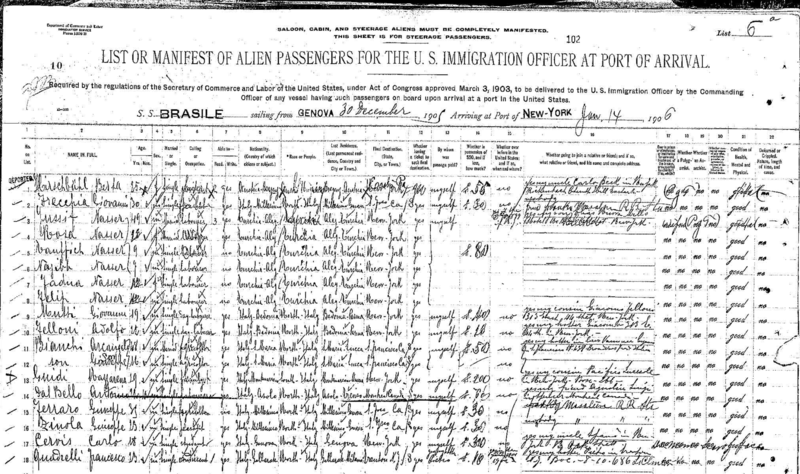

More information has survived about Yūsuf Naṣr’s second journey to America, this time with his entire family, than from his first crossing in 1901. His passport confirms that the group left Beirut for Alexandria on 24 November 1905.[30] Their first port of call was Genoa on Italy’s north-west coast, where shipping company agents could transfer their passengers directly onto one of the company’s transatlantic fleet for the New York run.[31] In fact, Yūsuf Naṣr switched companies, for reasons that are not clear. They had tickets for the Genoa–New York crossing aboard the SS Liguria on 22 December 1905 but, though all the family’s names were registered in the passenger manifest, all were firmly crossed out without explanation.[32] Having waited another eight days in transit limbo, however, the family finally departed for America aboard the SS Brasile on 30 December, stopping to collect several hundred more passengers in Naples on New Year’s Eve and finally arriving in New York, after a relatively slow crossing, on 14 January 1906.[33]

1903 poster advertising the ‘express transatlantic services’ offered by the La Veloce line from Genoa and Naples Public domain

The details of the manifest are fascinating. The six family members are identified as Yussif Nasser, a 49-year-old ‘Labourer’, even though his Ottoman passport (see ‘Exit from the Unbeloved Empire’, Fig. 7) declared his Trade (sanʿatı) to be ‘Clergy’ (mutesayyib, lit. ‘pious’). He was travelling with his 25-year-old wife Rosa (warda is Arabic for ‘rose’) and Yūsuf’s children from his first marriage, Tauffich, Najibb, Fadwa and Felipp. Almost all their names would be reinvented as part of the family’s Americanisation.[34] Somehow unrecorded in the passenger manifest, however, Warda/Rose had a fourth child with her, an infant daughter, and was heavily pregnant with another girl, born just a month later in the first phase of Rose’s new and long life in America. Their ‘Last Residence’ is given quite accurately in the manifest as ‘Aley-Turchia’, i.e. ʿAleih in the Turkish administrative region of Mount Lebanon. Between them they had $80 in cash, considerably less than on Yūsuf Naṣr’s first voyage. Yūsuf Naṣr misremembers the dates of his previous trip to America, giving 1898–99 instead of 1901–2. He states that the group are to rejoin his son Elias, resident at the Mills Hotel at 160 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village: subsidised lodging where working men with meagre salaries could rent a tiny room for 20 cents a night and east for 15 cents a meal.[35] Meanwhile Naṣrī, now 16 years old and permanently renamed Joseph Nusser, was still at the Woody Crest boarding school in Tarrytown, confirmed by the 1905 New York State Census as a ‘Scholar’ and a de facto permanent resident.[36]

Passenger manifest for the SS Brasile, which sailed from Genoa in Italy on 30 December 1905 and arrived at the Port of New York 15 days later. Entries 3–8: Yussif, Rosa, Tauffich, Najibb, Fadua and Felip Nasser © Ellis Island Foundation

Joseph Nusser goes back on the road (1906–11)

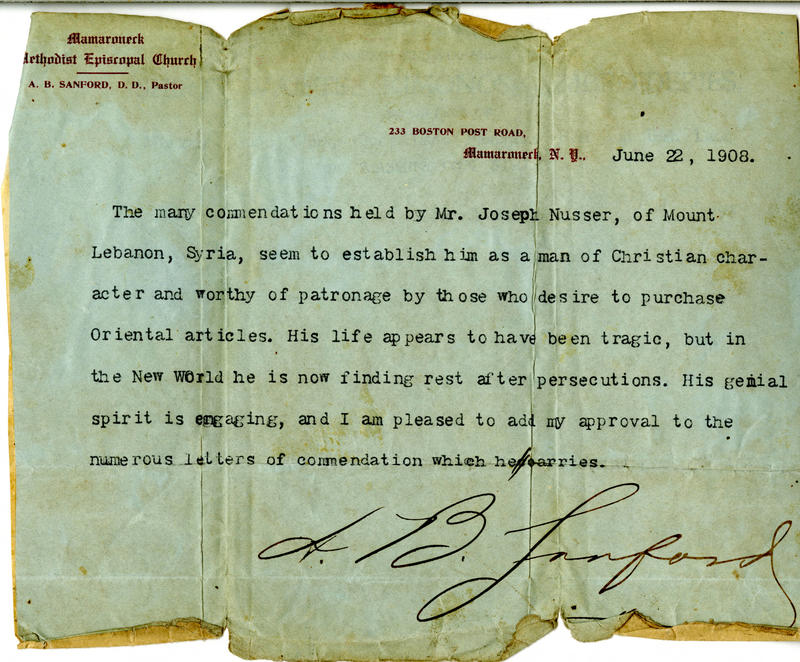

Once back in the city, it was not until 12 August 1906 that Yūsuf Naṣr – now, like his son, identifying as Joseph Nusser – began buying stock for the following year’s peddling season, making his first recorded purchase of silk, linen and lace from a young Lebanese entrepreneur, Tawfīq Farhūd, in Lower Manhattan.[37] T.S. Farhood & Co. of 81 Washington Street remained Joseph’s supplier of choice for four years.[38] Letters of recommendation preserved among his family papers indicate that he was back on the road by the early summer of 1907. No fewer than eleven letters were contributed that year by Presbyterian preachers across upstate New York, Pennsylvania and Connecticut, all citing Joseph’s previous excellent testimonials, upstanding character and persecution in his native country.[39] Fewer references were acquired in 1908: just five, one of them a repeat endorsement from the Rev. Irving White in Port Chester – and if the Rev. Otho Bartholow in Mount Vernon had been mistaken in blaming ‘the Mohammedan persecution’ for Joseph Nusser’s woes in Mount Lebanon, the letter’s recipient did not see fit to disabuse him.[40] In subsequent years, the endorsements dwindled to a trickle: just three in 1909 and one in 1911.[41] In some jurisdictions in Pennsylvania and upstate New York, formal licensing was in place to regulate out-of-town peddlers. Joseph collected and retained several of these: a typical example, from 10 March 1911, allowed ‘Rev. [sic] Jos. Nusser’ to sell his goods in Allentown on 11, 13 and 14 March only, subject to a fee of three dollars.[42]

Letter of recommendation dated 22 June 1908 from the Rev. A.B. Sanford of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Mamaroneck, NY © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

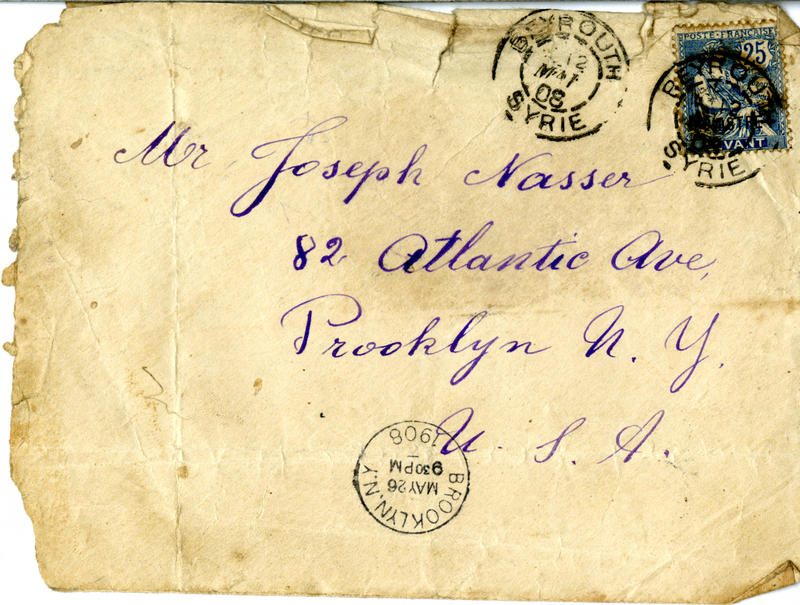

Joseph Nusser had rejoined the ranks of countless Lebanese immigrants who adopted the arduous lifestyle of the itinerant peddler. With business going well, he was able to move his family away from the crammed and unhygienic tenements of Lower Manhattan to the relative comfort of Brooklyn, like so many first-generation New Yorkers whose resources and prospects had improved.[43] The 1910 US Census records his address as 82 Atlantic Avenue, close to the docks where the East River flows out into the Upper Bay.[44] While home was in Brooklyn, however, his suppliers were consistently in Little Syria. For the 1910 season, he changed his main supplier of merchandise to Wader Bahūt, purveyor of General Oriental Goods at 35 Broadway.[45] For 1911-12, his last recorded purchases for his last year based in New York City, he switched again to Wadie Saadi, ‘Goldsmith and Jeweler’, at 107 Washington Street.[46] By June 1911, the family had moved a five-minute walk south, to 10 Verandah Place, near the green space of Cobble Hill Park.

Envelope addressed to Joseph Nusser in Brooklyn. The letter inside, dated 9 May 1909 and from Salīm Naṣr, owner of a literary bookshop in Beirut, is addressed to ‘My dear sister Mrs Warda Naṣr’ © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum, Nusser_F7_005a–c

Family tragedies (1906–12)

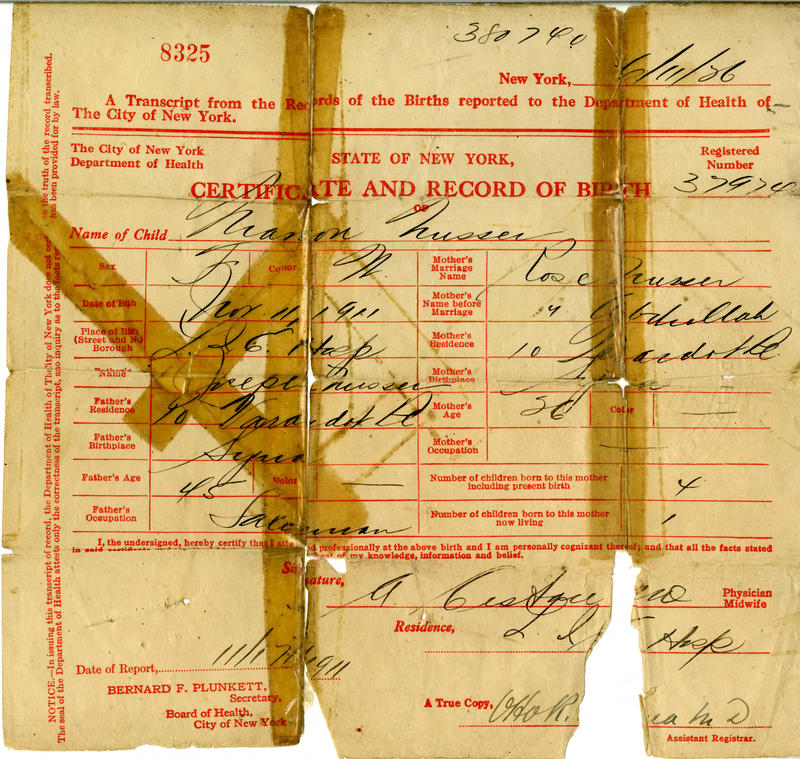

If Joseph Nusser had hoped that Brooklyn would mean health as well as prosperity, he was harrowingly disappointed. It is difficult to unpick the details from the limited documents available in the public domain but by 1912 Rose had lost all four of her children – three of them under the age of two and one just over.[47] The cause may well have been diphtheria, a ‘highly contagious, lethal and mysterious’ disease, or tuberculosis, ‘the most destructive killer in the city’.[48] The first of these fatalities, hard on her arrival in America, was Rose’s new baby, a boy named Jād, who died at just five days old on 25 January 1906.[49] These losses may have helped persuade Joseph Nusser to retire and move to Michigan. The supplementary documents in the family collection that describe his nomadic door-to-door salesman lifestyle dry up in 1912, the last year in which extant correspondence finds Joseph still resident in Brooklyn.[50] Rose had given birth to a fifth child, Marion, on 11 November 1911 - the first to survive into adulthood - and was doubtless concerned about her daughter's prospects for a healthy life in New York. But the final straw may have been the death of Fadwa on 12 February 1913 at the age of 16. Stricken with tuberculosis, she died at Polhemus Memorial Clinic, an extension of the Long Island College Hospital on the corner of Henry and Amity Streets, close to the Nusser home in Brooklyn.[51]

Birth certificate for Marion Nusser, Rose’s first surviving child. Joseph’s age is given as 45 when he was around 60 years old. It was Marion’s descendants who donated the family papers to the Arab American National Museum © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum, Nusser_F7_005a–c

The new Americans: Michigan, Ohio and Montana (1917)

By the 1920 US Census, most of the Nussers were resident at 360 St Aubin Avenue in Detroit, three blocks from the Detroit River waterfront.[52] They were becoming an all-American family. Elias was already a citizen – resident in Wyoming but having lived for several years and married in Montana – and his siblings followed over time. In March 1917, the 35-year-old Tewfik, still an automobile worker and now also resident in Detroit, the heart of the US car industry, made his formal application for naturalisation, renouncing forever ‘all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, and particularly to Mehmed V Emperor of the Ottomans’.[53] His brothers did so too, in different parts of the US. Joseph Jr. was living in Youngstown, Ohio, when he registered for the draft in January 1917, confirming that he was a ‘Declarent’, i.e. his application formally registered to become a US citizen.[54] Ned Nusser, whose life would take him to California and Utah, was in Meagher, Montana, when he filled out the same paperwork.

Tawfīk/Tom Nusser, photographed at an unknown location, c. 1912–13 © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum, Nusser_F17_009a

Joseph Nusser: Lebanese to the end (c. 1851–25 July 1924)

Unlike his children, there is no evidence that Joseph Nusser himself ever sought American citizenship during the final eighteen years of his life in Detroit. He may have feared, with good reason, that, were he to regain ownership of his family farm in Mount Lebanon, his children would be barred from inheriting it.[55] Joseph certainly never forgot his grievances back home, maintaining a protracted correspondence with lawyers in Beirut until shortly before his death.[56] But his descendants have, over the past century, spread across the US. Few of his grandchildren survive today but there are dozens of great-grandchildren and possibly hundreds of great-grandchildren from California to the Eastern Shore, some of whom are proud to know that the preacher whose feet first touched America in the early summer of 1901 left such an impactful human legacy.

[1] Arab American National Museum (henceforth AANM), Joseph Nusser Family Collection (henceforth JNFC): https://aanm.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16806coll13.

[2] Additional manuscript sources were provided directly to me by Yūsuf Naṣr’s descendants in seven tranches, cited where appropriate as Monterastelli Family Collection, A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2 and C3.

[3] An article on Yūsuf Naṣr's persecution, ostracism and exile, based closely on his hand-written memoir, has been submitted to an academic journal for consideration.

[4] Leila Fawaz, An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

[5] Feras Krimsti, ‘The Massacre in Damascus, July 1860’ in David Thomas and John Chesworth (eds.), Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History. Volume 18. The Ottoman Empire (1800-1914) (Leiden: Brill, 2021), 378–406.

[6] Engin Deniz Akarlı, The Long Peace: Ottoman Lebanon, 1861–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 31–3. The full French text of the protocol and its subsequent amendments can be found in Pierre Dib, L’Eglise Maronite: Les Maronites Sous les Ottomans: Histoire Civile: Tome II (Beirut: Maronite Archdiocese, 1962), 587–605.

[7] Selim Deringil, Conversion and Apostasy in the Late Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: CUP, 2012), 79.

[8] Rev. H. Dwight, ‘Translation of the Firmân of his Imperial Majesty ʿAbd-el-Mejîd, Granted in Favor of his Protestant Subjects’, Journal of the American Oriental Society (hereafter JAOS) 3 (1853), 218–20, and ‘Translation of the Firmân Granted by Sultân ʿAbd-el-Mejîd to His Protestant Subjects’, JAOS 4 (1854), 443–4.

[9] Devrim Ümit, ‘The American Protestant Missionary Network in Ottoman Turkey, 1876-1914’, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 4/6 (2014). See also Thomas Laurie and Henry H. Jessup (eds.), A Brief Chronicle of the Syria Mission (Beirut: American Mission Press, 1901), and Adele L. Younis, The Coming of the Arabic-Speaking People to the United States (ed. Philip M. Kayal) (New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1995), 37–49.

[10] Frances E. Scott, Dare and Persevere: The Story of One Hundred Years of Evangelism in Syria and Lebanon, from 1860 to 1960 (London: Lebanon Evangelical Mission, 1960) and J.D. Maitland-Kirwan, Sunrise in Syria: A Short History of the British Syrian Mission, from 1860 to 1930 (London: British Syrian Mission, 1930).

[11] James S. Dennis et al. (eds.), World Atlas of Christian Missions (New York: Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions, 1911), 92.

[12] Rufus Anderson, History of the Missions of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to the Oriental Churches (2 vols., Boston: Congregational Publishing Society, 1872 and 1874), ii, 370.

[13] James A. Dennis, A Sketch of the Syria Mission (New York: Mission House, 1872), 8.

[14] Jeremy Salt, ‘Trouble Wherever They Went: American Missionaries in Anatolia and Ottoman Syria in the Nineteenth Century’, The Muslim World 92/3–4 (2002), 295–6.

[15] Sophia Lloyd, ‘Life of Mrs [Augusta] Mott, 1892’, Middle East Christian Outreach Box 11 (1st series), Centre for Muslim-Christian Studies, Oxford (12 vols.), vii, 265, and x, 386.

[16] ‘List of Officers in the British Syrian Mission in Syria for the Year ending 30th June, 1893’, Daughters of Syria: British Syrian Mission Schools and Bible Work, Quarterly Record October 1893, 1–3.

[17] For overviews of this phenomenon, see Élie Safa, ‘L’Émigration Libanaise’, Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut) PhD thesis, 1960; A. Deniz Balgamiş and Kemal Karpat, Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 2008); and Engin Deniz Akarlı, ‘Ottoman Attitudes Towards Lebanese Emigration, 1885-1910’, in The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration (eds. Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi) (London: Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1992), 109–38.

[18] Viscount de Petiteville to Alexandre Ribot, French Foreign Minister, 1 April 1890: Adel Ismaïl (ed.), Documents Diplomatiques et Consulaires Relatifs à l'Histoire du Liban: Et des Pays du Proche-Orient du XVII Siècle à Nos Jours (21 vols., Beirut: Éditions de Oeuvres Politiques et Historiques, 1975–83), xv, 428–9.

[19] Riccardo Liberatore, ‘Shipping Migrants in the Age of Steam: The Rise and rise of the Messageries Maritimes c. 1870–1914’, Global History of Capitalism Project, University of Oxford, September 2018: https://globalcapitalism.history.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/globalcapitalism/documents/media/case_05_-_shipping_migrants_in_the_age_of_steam.pdf?time=1537187426375. See also Süleyman Uygun, ‘The Messageries Maritimes Company in the History of Transportation in Istanbul’, History of Istanbul, Vol 6. Transportation and Communication, 508–19: https://istanbultarihi.ist/589-the-messageries-maritimes-company-in-the-history-of-transportation-in-istanbul.

[20] Rev. Dr. James Dennis first worked in Syria as a missionary, then as Professor of Theology at the newly established Beirut Theological Seminary: William H. Berger, ‘James Shepard Dennis: Syrian Missionary and Apologist’, American Presbyterians 64/2 (1986), 97–111.

[21] Céline Regnard, En transit: Les Syriens à Beyrouth, Marseille, Le Havre, New York, 1880-1914 (Paris: Anamosa, 2022).

[22] The Ellis Island processing record gives the day after the La Champagne docked, 6 May 1901, as the immigrant’s formal arrival date: https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiNjA1MjgzMDEwMDgzIjs=/czo5OiJwYXNzZW5nZXIiOw==. See also Morton Allan Directory of European Passenger Steamship Arrivals for the Years 1890 to 1930 at the Port of New York and for the Years 1904 to 1926 at the Ports of New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Baltimore (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987), 79, and Frank C. Bowen, A Century of Atlantic Travel, 1830-1930 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1932), 177-8.

[23] Linda Jacobs, Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880–1900 (New York: Kalimah Press, 2015), 180 and 188–9.

[24] Listing of ‘Commission Merchants’: Salloum A. Mokarzel and H.F. Otash (eds.), The Syrian Business Directory (New York: Mokarzel and Otash, 1908), 7, cited in Gregory J. Shibley, ‘New York’s Little Syria, 1880-1935’, Florida Atlantic University MA thesis, 2014, 52–3. Constantine [al-]Biskinti’s surname suggests that he was from the village of Biskintā, around 50 km from Bdādūn on twisting hill roads, although the directory entry gives his Lebanese counterpart address as Kousba El Koura, even further north.

[25] Woody Crest Monthly, November 1901, 1–2: Helen Miller Gould Shepard Papers, MS 1422, Series V, Container 1, Box 7, New York Historical Society.

[26] Reports on the community were regular features in the local press: see, for example, ‘New-York’s Syrian Colony’, New-York Tribune, 13 March 1898, 4–5, Cromwell Childe, ‘New York’s Syrian Quarter’, New York Times Magazine, 20 August 1899, 4–5, and ‘Sights and Characters of New York’s “Little Syria”’, New York Times, 29 March 1903, 32.

[27] On Carson’s life, see ‘Dr. J.F. Carson, Noted Pastor, Dead: Occupied Pulpit of Central Presbyterian Church, Brooklyn, for Four Decades’, New York Times, 3 September 1927, 15.

[28] AANM, JNFC, Nusser_F6_002a.

[29] Quotation ascribed to the lawyer Iskandar Bārūdī: AANM, JNFC, Folder 14: ‘Life Story’, 26.

[30] AANM, JNFC, Nusser_F2_001b.

[31] A letter from Mr. de Clercq, French Consul-General in Genoa, to Théophile Delcassé, French Foreign Minister, 6 December 1902, provides a vivid snapshot of the scene at this busy migration hub: Ismaïl, Documents diplomatiques et consulaires, xvii, 208–9.

[32] The Liguria was run by the Navigazione Generale Italiana (Italian General Navigation) company, another competitor for the transatlantic migrant trade. Yūsuf is recorded incorrectly as Mussa (a ‘Mercator’ or merchant); the other family members are listed as Rosa, Tawfik, Najib, Fadwa and Felip. In the space for ‘Relative or friend’ in the US, the manifest records ‘Son and brother, Nasser, Josef, Woody Crest, Box 410, Tarrytown, New York’: Ellis Island Passenger Search online facility: https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAyMTY4MDQwMTY5Ijs=/czo5OiJwYXNzZW5nZXIiOw==.

[33] Ellis Island Passenger Search online facility: https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAyOTA4MDUwMTIzIjs=/czo5OiJwYXNzZW5nZXIiOw==. The SS Brasile, run by the Genoa-based La Veloce Navigazione Italiana a Vapore (Fast Italian Steam Navigation), was a new Italian-built vessel that stopped in New York on its way to South America. See Morton Allan Directory, 114, for all the company’s 1906 Genoa-New York crossings.

[34] Tawfīq changed his name to Thomas in America. His date of birth, 8 June 1891, means that he was 14½ years old at this time, not 9 as given on the manifest. Najīb also changed his name, to Edward. His date of birth, 18 August 1893, means that he was 12½ years old, not 7 as given on the manifest. Fadwa, known also as Anna, was born on 2 February 1897, so was nearly 9 at this time. Philippe (born 8 July 1898) was over 7 years old at the time of his arrival in America.

[35] Paul Groth, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 149–50. For an account of the hotel’s opening in October 1897, see ‘Waldorf of the Slums’, Philadelphia Times, 28 October 1897, 3. Elias Nusser was on the verge of becoming a naturalised American citizen: Supreme Court of New York County, Bundle 301, Record No. 61: ‘Petition of Elias Joseph Nusser to be Admitted as a Citizen of the USA’, dated 3 April 1906, via ancestry.com (accessed on 14 August 2023).

[36] The census mistakenly identifies Joseph as a US citizen: New York State Census, 1905, Westchester > Greenburgh > Third Election District, via ancestry.com (accessed on 17 September 2023).

[37] Tawfīq Saʿīd Farhūd (1884–1975) arrived in New York in 1902 and established his business in Little Syria with impressive speed: author’s research on ancestry.com, September 2023.

[38] Joseph Nusser subsequently ordered supplies on 9 March 1907, 23 March 1907, 22 July 1907, 25 November 1907, 14 September 1908, 9 March 1908, 17 April 1908, 27 May 1908, 13 July 1908, 1 September 1908, 15 November 1908 and 28 August 1909: AANM, JNFC, Folder 9: Receipts.

[39] Letters from Alfred Griffin, Trinity Clergy House, 61 Church St., New York (May 1907); Frank J. Milman, The Manse, Second Presbyterian Church, 415 Garfield Square, Pottsville PA (25 May 1907); G. Archibald Humphries, First Presbyterian Church, Tamaqua PA (29 May 1907); J.E. Freeman, East Mauch Chunk PA (1 June 1907); D.A. Winter, Zions Reformed Church, Lehighton PA (5 June 1907); Frank F. German, Saint Thomas's Church, Mamaroneck NY (22 June 1907); Irving E. White, Port Chester NY (26 June 1907); John G. Davenport, Second Congregational Church, Waterbury CT (22 July 1907); J.A. Biddle, St John’s Church, Waterbury CT (22 July 1907); Saul O. Curtice, First Methodist Episcopal Church, South Norwalk CT (7 August 1907); and Herbert S. Brown, Parsonage of the Congregational Church, Darien CT (30 November 1907): AANM, JNFC, Folder 6: Letters of Reference.

[40] Letters from Irving E. White, Presbyterian Church, Port Chester NY (11 March 1908); Otho F. Bartholow, First Methodist Episcopal Church, Mount Vernon NY (17 May 1908); Harry H. Beattys, Chester Hill Methodist Episcopal Church, Mount Vernon NY (9 June 1908); Joseph H. Selden, The Parsonage, Second Congregational Church, Greenwich CT (22 June 1908); and A.B. Sanford, Mamaroneck Methodist Episcopal Church, 233 Boston Post Road, Mamaroneck NY (22 June 1908): ibid.

[41] Letters from F. Branklerck, Grace Church Rectory, White Plains NY (15 February 1909); Irving E. White, Port Chester NY (18 August 1909); A.F. Schauffler, New York Mission & Tract Society, 105 East 22nd St., New York (15 December 1909); and David James Burrell, Marble Collegiate Church, 5th Ave. and 29th St., New York City (29 March 1911): ibid.

[42] Licenses from Bronxville NY (5 May 1908 and 23 August 1910); Allentown PA (10 March 1911); and Mount Vernon, NY (I the name of Elias Nasser, 13 November 1912): AANM, JNFC, Folder 9: Peddler's Licenses.

[43] Jacobs, Strangers in the West, 334 ff.

[44] The household is listed as including Rose, Joseph Jr. (now 22), Tawfīq (not yet ‘Tom’, a machinist at an auto shop), Ned (no longer Najīb; an ‘alaroundman’ at a laundry), Fedwa, Philippe and George, born on 7 February 1909: Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910–Population, New York > Kings > Brooklyn Ward 6 > District 0053 (18 April 1910).

[45] Yūsuf ordered supplies from W.J. Bahoot in two batches on 29 June 1910: ibid., Folder 9: Receipts.

[46] Orders on 10 September 1910, 22 December 1911 and 11 June 1912: ibid.

[47] Notes on ‘Rose Owen or Aoun Nusser Hackim [her second husband’s surname]’: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/105107426/rose-nusser_hackim.

[48] Tuberculosis was New York’s leading killer when the Seaview Tuberculosis Hospital was opened in Staten Island in 1913. One academic study notes that the disease, which ‘struck the young disproportionately’, was and ‘the death rate in the poorest areas was almost twice what it was for the city as a whole’: Daniel M. Fox, ‘Social Policy and City Politics: Tuberculosis Reporting in New York, 1889–1900’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 49/2 (1975), 169–95. On the campaign against diphtheria, see Perri Klass, ‘How Science Conquered Diphtheria, the Plague Among Children’, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2012: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/science-diphtheria-plague-among-children-180978572/.

[49] Neither birth certificate (No. 8095) nor death certificate (No. 3218) have a name, only describing the infant as ‘Male Nasser’.

[50] Letter from Lebanon dated 23 August 1912: AANM, JNFC, Folder 7: Joseph Nusser Correspondence, Nusser_F7_032b.

[51] Joseph H. Raymond, History of the Long Island College Hospital and Its Graduates, Together with the Hoagland Laboratory and the Polhemus Memorial Clinic (Brooklyn, Association of the Alumni, 1899), 68–75.

[52] Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920–Population, Michigan > Wayne > Detroit Ward 9 > District 0276 (accessed 8 January 1920).

[53] U.S. Department of Labor Naturalization Service, Eastern District of Michigan, dated 19 March 1917, via ancestry.com (accessed September 2023). Tawfīq’s date of birth is given as 8 June 1891.

[54] World War I Draft Registration Card, 1917–1918, Ohio > Youngstown City > 3 > Draft Card N, Registration Card 1351, No. 82, via ancestry.com.

[55] A letter from A.W. Terrell, U.S. Legation in Constantinople, to John Sherman, US Secretary of State, dated 30 April 1897, states that ‘under article 111 of the Turkish law of April 21, 1858, which relates to real estate, land once owned by a Turkish subject who has abandoned his nationality does not descend to his children’: Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States 1897 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1898), 588.

[56] AANM, JNFC, Folder 5: ‘Legal Correspondence with the Appeals Court of Mount Lebanon’; Folder 7: ‘Joseph Nusser Correspondence’; Folder 12: ‘Various Documents and Correspondence I’; and Folder 13: ‘Various Documents and Correspondence II’.