‘Exit from the Unbeloved Empire’: Ottoman Passports and Mass Emigration from Mount Lebanon

This brief appraisal of the Ottoman passport in the context of mass emigration from Mount Lebanon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries arose from the discovery of a passport belonging to a traveller named Yūsuf Naṣr Muraʾib in the digitised collection of the Arab American National Museum (Fig. 7). This discovery prompted me to investigate the role of a document that was designed to restrict movement within the Ottoman Empire but was instead used to enable the departure of tens of thousands of people from the region to a wide range of destinations, including the United States, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Western Europe and Australia. There is a suggested reading list at the end of the article.

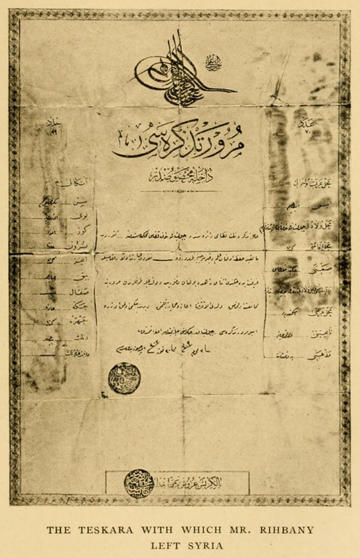

Fig. 1: Abraham Rihbany, A Far Journey, p. 172

‘The problem of a teskara (passport), without which I could not legally leave the country, next confronted us. … If the teskara failed to come, should I give up going to America, or expose myself to the penalty of an unjust law and to being disgraced by trying to leave the country as a fugitive? … [Then] our most important task was to secure the indorsement of our teskaras by the Beyrout officials. Difficulties were often placed in the way of emigrants from Turkey by the officials for the purpose of extorting money from them. Emigration to America was discouraged and generally supposed to be prohibited. Our passports indicated that our destination was Alexandria, which was true, but not the whole truth. Moreover, our more refined speech and manners seemed to remove us, in the minds of the officials, from the ordinary class of emigrants. For the indorsing of our passports we were required to pay half a madjidy — Turkish dollar — each, and we thought our exit from the unbeloved empire was rather cheap.’ (Abraham Rihbany, A Far Journey (1914), pp. 167 and 171)

Abraham Rihbany’s experience in early 1892 reminds us that travel within and beyond the Ottoman Empire required a considerable amount of official paperwork. This began with a simple identity document but a would-be migrant then needed to obtain a character testimonial from a trusted local source before obtaining his or her formal travel permit. When imperial officials actively tried to prevent emigration, travellers either had to lie about their real destinations or bribe local officials to obtain passports. Above all, it is essential to understand that the Ottoman passport was designed by administrative officials in Istanbul as an instrument of physical constraint – so those officials would have seen the widespread exploitation of passports by would-be emigrants to leave the empire as the misuse of an imperial instrument and a highly subversive act. Residents of the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate already lived in a specially designated territory that had its own bespoke rules of government, designed precisely to suppress popular discontent and agitation: opting to leave it while bearing a document headed with the tughra of the Sultan himself was a double rejection of Ottoman authority.

The Ottoman authorities introduced the Passport Office Regulation (Pasaport Odası Nizamnamesi) on 14 February 1867, mandating formal documentation for anyone entering, travelling within or leaving the empire’s vast territories. The new documentation was both a vehicle for bureaucratic data management and an instrument of state control and surveillance. The new legislation was more than 20 years in the making, updating regulations that sought to control the mobility of Ottoman nationals dating back to 10 February 1841. Passport law was one aspect of the much wider Tanzimat reforms: an intensive root-and-branch modernisation of the constitution, the law, the army, land management systems, inter-religious relations and the education system across the empire. This drive to create a new kind of body politic and a new collective identity in the face of European competition continued and developed into the post-Tanzimat era of Sultan Abdülhamid II – and passports were an important part of the national project. But, as İlkay Yılmaz notes, the combination of documentation that both recorded identity and controlled mobility with a programme of regular census taking – in other words, an empire-wide system of data gathering – had been an increasingly sophisticated aspect of Ottoman bureaucracy since the beginning of the nineteenth century.

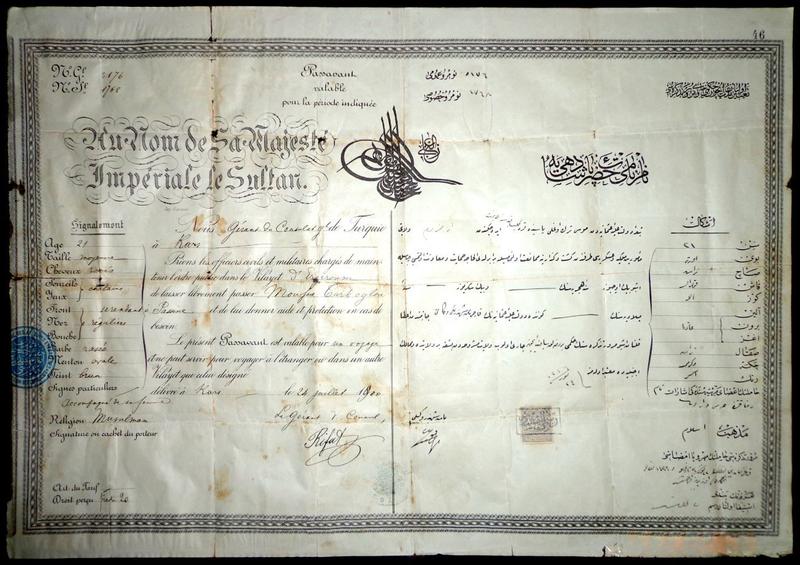

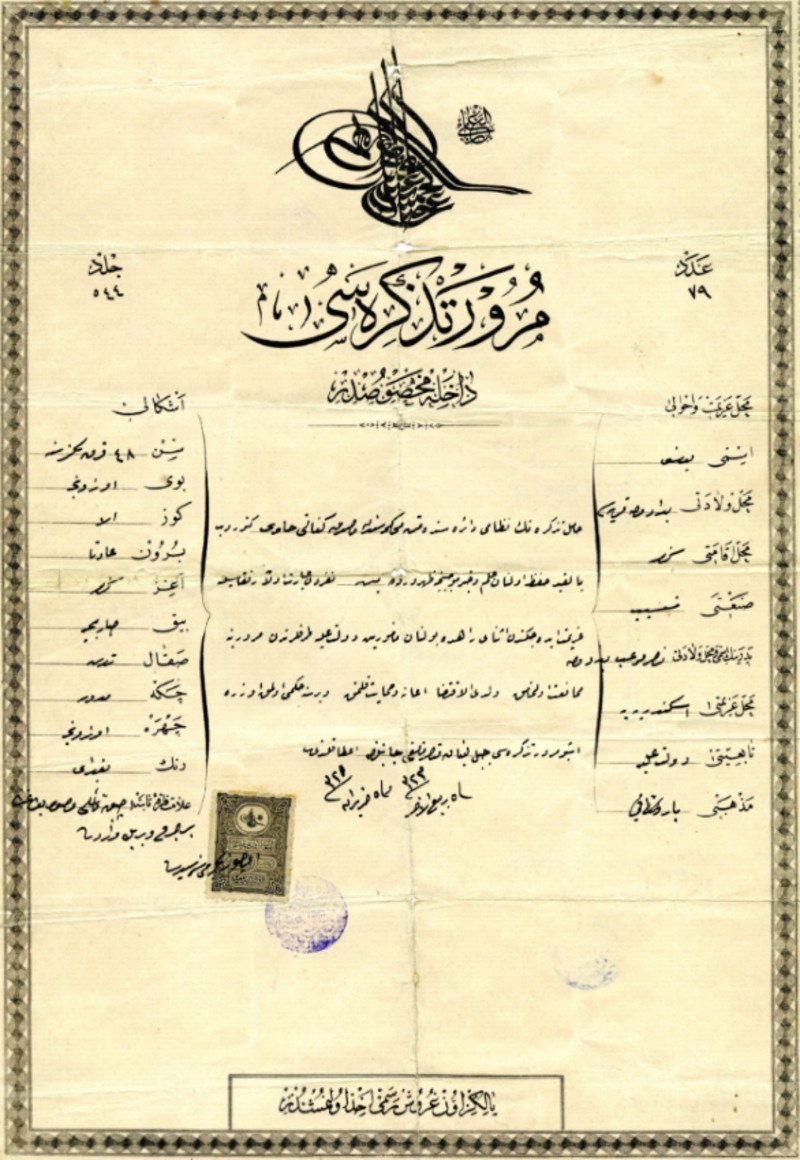

The passport itself, known as a passage permit (mürur tezkiresi), was primarily a laissez-passer for internal journeys, designed primarily to control movement from an individual’s home vilayet to the imperial capital at Istanbul. With administrative reforms leading to increased centralisation, such documentation fell under the purview of the Travel Permit Office (Mürur Kalemi) at the Interior Ministry. Foreign travel was of only secondary concern, although Articles 1 and 5 of the new law stated clearly enough that anyone who wanted to enter or leave Ottoman territory was required to obtain a passport from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Article 10 added that ‘anyone who wants to travel to foreign countries from Ottoman territory will not be allowed to go unless they bring their [internal] passport to the Liman Odasına [Port Authority] in Dersʿādet [Istanbul] or to the relevant officer in other locations.’ Some travel documents, indeed, explicitly prohibited travelling abroad. A passport issued by the acting Turkish Consul in Kars to Moussa Turkoglou on 24 July 1900 (Fig. 2) allowed the bearer to travel within the vilayet of Erzurum, in north-eastern Turkey, but added in the final paragraph of the central prescription: ‘This pass [passavant, not passeport] is valid for one journey and cannot be used to travel abroad or in a Vilayet other than the one designated here.’

Fig. 2: Passport in the name of Moussa Turkoglou, issued on 24 July 1900 Public domain

In the wake of the 1867 legislation, acquisition of a passport depended on the applicant producing two documents. The first was another recent introduction: the new national identity document (tezkere-i osmaniye) that was mandatory for all official business, such as property transactions, everywhere in the empire. Kemal Karpat has noted that the primary function of the 1866 census was to enable provincial officials to ensure that every citizen could then be obliged to obtain this new document of state supervision. This prototype ID card contained the vital information that would then be copied onto a traveller’s passport: name (ismi); age (sin); birthplace (mahall-i veladeti); father’s name and birthplace (pederinin ismi ve mahall-i veladeti); and religious affiliation (mezheb).

The second qualifying document was an ilmühaber, a signed notification of the bearer’s respectability defined by İlkay Yılmaz as a ‘proof of good behavior in the framework of traditional social control mechanisms’: those social mechanisms were then effectively co-opted in the name of state security ‘in order to guarantee the accuracy of the reported information’. This certificate or letter of endorsement provided additional details, such as marital status and the names of any immediate family members, and had to be signed by a figure of recognised authority within an individual’s social grouping. Military personnel would secure theirs from a senior officer, religious students from the head of their medrese, Muslims citizens from their local imam or village lay headman (muhtar), and any non-Muslim from his or her metropolitan, patriarch, rabbi or other millet-specific religious personality. The ilmühaber had legal applications in areas as diverse as healthcare management and land rights but in the wider context of imperial security, what started as a traditional confirmation of good social standing in a given community evolved rapidly, in parallel with the new identity document, to become an additional tool of social control by the state. Travelling without a valid passport put an individual at risk of prosecution under vagrancy laws and/or being pressed into military service.

The passports that were then issued were written by hand, in Ottoman Turkish and/or French, on a printed template bearing the seal of the Sultan and the office of the issuing authority. It is worth noting that the documents carried by Abraham Rihbany in 1892 (Fig. 1) and Yūsuf Naṣr Muraʾib in 1905 (Fig. 7) are identical, suggesting that the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate used the same printed template for at least two decades. Such passports were usually valid for a maximum of one year. As well as copying the holder’s persona details from his or her ID document, the mürur tezkiresi included, variously, one-word descriptions of the bearer’s height (boy), eyes (göz), nose (burun), moustache (bıyık), beard (sakal), chin (çene), face (çehre), complexion (renk), as well as any distinguishing marks (ʿalâmet-i fârika-i sabite). With the arrival of photographs as easily obtainable proofs of identity, the late nineteenth century Ottoman document evolved to become a hybrid of the old internal laissez-passer and the new European passports.

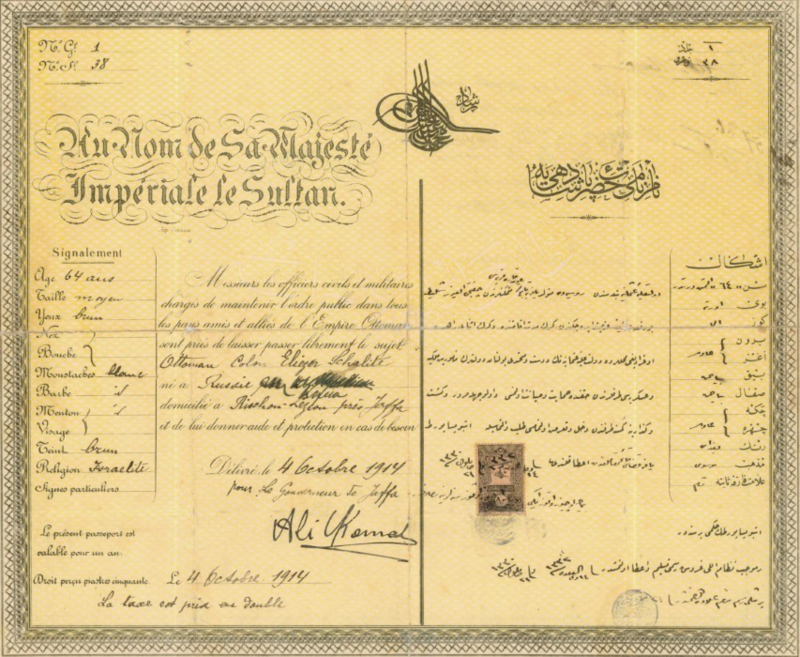

Fig. 3: Passport issued to a Russian Jewish settler ('colon'), Eliezer Schalite, at Jaffa on 4 October 1914 Public domain

As well as covering the internal movements of its own citizens, sometimes travelling across the full breadth of the imperial dominions, the 1867 legislation also dealt with travellers from outside. These included Sunni, Shiʿi and Christian pilgrims – visiting, respectively, the holy sites at Mecca and Medina, Najaf and Kerbala, Jerusalem and Bethlehem – as well as aristocrats enjoying the further reaches of the Grand Tour and more conventional tourists seeking first-hand experience of the eastern exoticism that they had read so much about in the pages of interior design magazines and racy fiction. But not all incomers were welcome and the basic passport controls were tightened severely under specific circumstances. Ottoman police already exercised considerable powers over travelling citizens under the Police Law (Zaptiye Nizamnamesi) of 20 March 1845 – and the 1871 Regulation Bill on Passport Procedures (Pasaport Kalemleri Nizamname Layihası) additionally gave them responsibility for issuing Ottoman internal passports to foreigners bearing their own national passports.

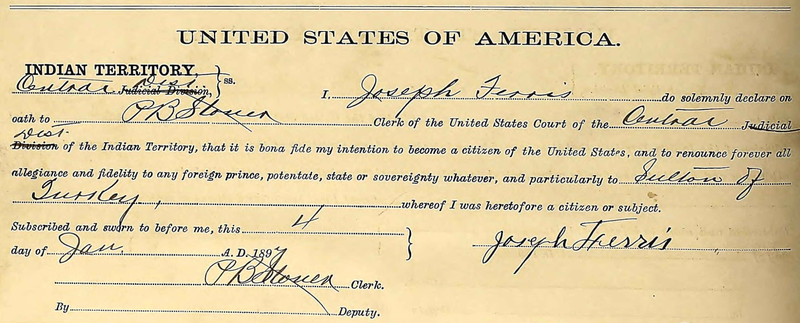

Perhaps because Ottoman officials in Istanbul itself were not yet aware of the accelerating scale of mainly Maronite Christian emigration from the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate, early passport legislation featured no explicit penalties for nationals leaving the empire without the official sanction afforded by valid documentation. This omission was swiftly remedied but only in the case of Ottoman nationals assuming an alternative nationality. Anyone pursuing naturalisation in the United States, for example, was required to renounce formally their previous nationality. In one surviving certificate (Fig. 3), Joseph Ferris, formerly Yūsuf Fāris of Mount Lebanon, declares his bona fide intention ‘to renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty whatever, and particularly to [the] Sultan of Turkey, whereof I was heretofore a citizen or subject’.

On 19 January 1869, a new Ottoman Citizenship Law (Tabiiyet-i Osmaniye Kanunnamesi), one of the foundation stones of a new collective Ottoman identity, addressed the problem. Articles 5 and 6 were definitive, warning that if an Ottoman national acquired another nation’s citizenship without official consent from Istanbul, the authorities there reserved the right to terminate his or her Ottoman nationality – in which case the traveller would not be allowed to return to the empire. The law that established a common Ottoman citizenship, irrespective of ethnicity or religion, for the first time, thus threatened in the same breath to take it away. This threat was primarily aimed at Armenians, especially those who returned from America with a view to fomenting unrest within the empire. Articles 5 and 6 also had their origins in the state’s long-held frustrations about Ottoman subjects claiming various kinds of foreign diplomatic protection – a successful Damascus businessman, for example, with powerful friends in the British government, or an aggrieved member of a vulnerable millet seeking assistance from Paris – and thereby undermining the Ottoman state. US State Department officials were repeatedly engaged in correspondence with their Ottoman counterparts about the rights and protections of naturalised US citizens returning to Turkey or one of the imperial provinces.

Fig. 4: Joseph Ferris forswears his loyalty to the Ottoman Sultan, 4 January 1897 © Oklahoma Historical Society

The 1869 legislation did not, however, elaborate on the citizenship status of an individual who travelled abroad without a passport, who did not seek naturalisation elsewhere and who intended to return, having either remitted money from employment overseas and/or made sufficient savings to enable a more secure life back within the empire. Nor did the publication of new passport-specific legislation, the Pasaport Nizamnamesi, on 20 February 1884. Chapter 1.1 of this new law did again emphasise that ‘those who would travel to foreign countries from Ottoman territory are obliged to obtain a passport pursuant to the provisions of this regulation’ but specified no punishment for infraction. In practice, however, the threat of being rendered not just undocumented but stateless was real.

Two cases illustrate the response of Ottoman officials to nationals who returned, having left without legitimate documentation. In early 1886, eleven men from Mount Lebanon were denied entry to the US on the grounds of penury and ended up confined in Liverpool’s Brownlow Hill Workhouse. When the affair was brought to the attention of the Ottoman Ambassador to London (and former mutassarif of Mount Lebanon), Rustem Pasha Mariani, his response was entirely unsympathetic because the men ‘had permanently [à titre définitif] abandoned Turkey to settle in the United States’, they did not fit into 'the category of shipwrecked seafarers or other needy persons whose repatriation is provided for by consular regulations’ and had therefore forfeited the standard consular protections afforded an Ottoman national. After several months and under pressure from the British Foreign Office, Rustem’s superiors in Istanbul relented and authorised new passports for the eleven men, who left Liverpool for Beirut on 6 August 1886. A second case in 1903 featured another individual who was also rejected by US immigration officers at Castle Garden in New York on the grounds of poverty. In the case of Yūsuf Mikhāʿīl, customs officials back in the Levant were reported as being ‘puzzled’, because their understanding of the most recent legislation meant that he was barred from re-entering the empire after leaving without permission.

Even when the 1884 passport legislation was revisited a decade later – specifically aimed, according to Alim Akkoç, at preventing the use of the passport as a means of changing nationality – there were still no explicit punishments for those who broke the restated rule on passports for foreign travel. There were, however, two important modifications in the 6 December 1894 revisions. The first addressed vagrancy, a problem for state officials in Istanbul who worried that penniless and unskilled migrants in America jeopardised the prestige of the Ottoman Empire abroad. Article 9 stipulated that for ‘vagrants (serseri) who want a passport to go to foreign countries, if they incur expenses on returning to their home country, have to prove they have a guarantor to cover such expenses.’ The second change addressed the loss of a passport. Article 17 clarified that a returning Ottoman national who was brought before the Police Ministry in Istanbul (or relevant provincial passport office) would be given the opportunity either to prove his or her identity or to declare a guarantor: failure or inability to do so would mean a fine of double the passport fee or an outright ban on re-entering the country.

So how hard did Ottoman officials really try to stop the dramatic increase in emigration from the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate, especially its Maronite regions? The numbers were so remarkable that they were certain to attract the attention of the Ottoman authorities at mutasarrifate, vilayet and even national level. In the period between 1860 and 1900, several hundred thousand people, perhaps as much as a quarter of the population of Mount Lebanon, emigrated to the Americas, Europe, Australia and elsewhere in the Arab world – and the outflow only intensified between 1900 and the outbreak of World War I. Najeeb Arbeely, a Lebanese migrant who subsequently became a leading figure in the nascent Arab community in Lower Manhattan, described in July 1880 how accelerating migration numbers had led the Ottoman authorities to impose severe restrictions on travel documentation. ‘Passports are withheld,’ he told an American reporter, ‘and as no one is allowed to leave there without these documents, the disfavor amounts to really a prohibition.’ And as emigration continued to rise, the central Ottoman authorities attempted to rein in what had become chronic corruption in the passport application process. Officials tempted to take a bribe to enable travellers to ignore the ban were warned on 4 July 1892 that any officer found to have violated regulations and issued passports for internal or foreign travel three times in one year would be sacked.

Several historians have noted, however, that, even when a formal ban on emigration to the United States was announced on 14 March 1888, it was much more rigorously applied in respect of Armenians – in which context it had certainly been motivated – than Lebanese. As Céline Regnard has observed, officials dealing with Beirut and Mount Lebanon ‘administratively discouraged’ emigration, rather than banning it. David Gutman has pointed out the failure of successive local initiatives to control the issuance of even internal travel documents, suggesting that the Ottoman Interior Ministry simply gave up on Mount Lebanon. This may have been because they thought that thinning out a historically troublesome region may not be a bad thing – but it seems likely that Ottoman officials in the capital were simply far more preoccupied with managing the mobility of Armenians. In respect of bribery, despite Istanbul’s efforts to hold its provincial officials to a high standard of discipline, contemporary sources suggest that corruption continued to play a part in a vigorous passport industry. One French diplomat commented that, although emigration was ‘prohibited in Syria, for a long time Syrians, in return for a high fee paid into the hands of the Turkish authorities … obtain permission to leave … for a better lot in the two Americas.’ And when venal mutasarrifate officials charged the mainly European shipping companies a per capita fee for travellers boarding at the Port of Beirut, the companies, ‘anxious not to alienate the governor of a province which gives them 6,000 emigrants each year’, were only too happy to pass the fee on to the migrants. In the words of another French diplomat, ‘Like sheep mistreated in the fold, the Lebanese flock towards the exit door – but they cannot leave without being fleeced one last time.’

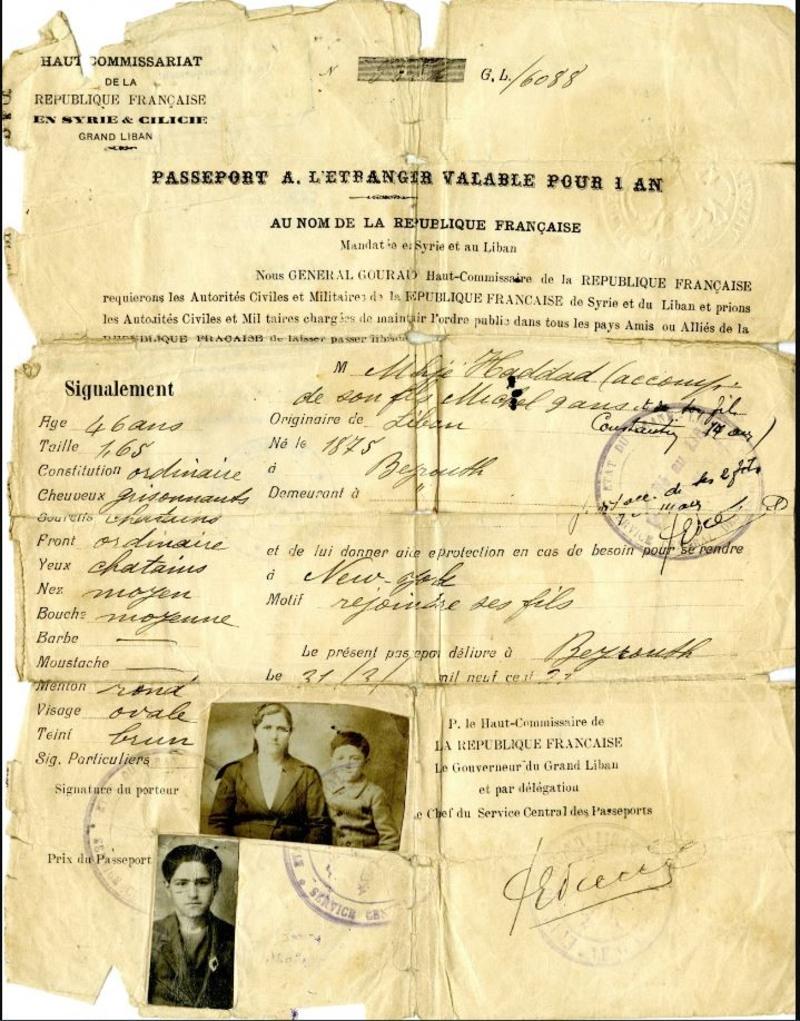

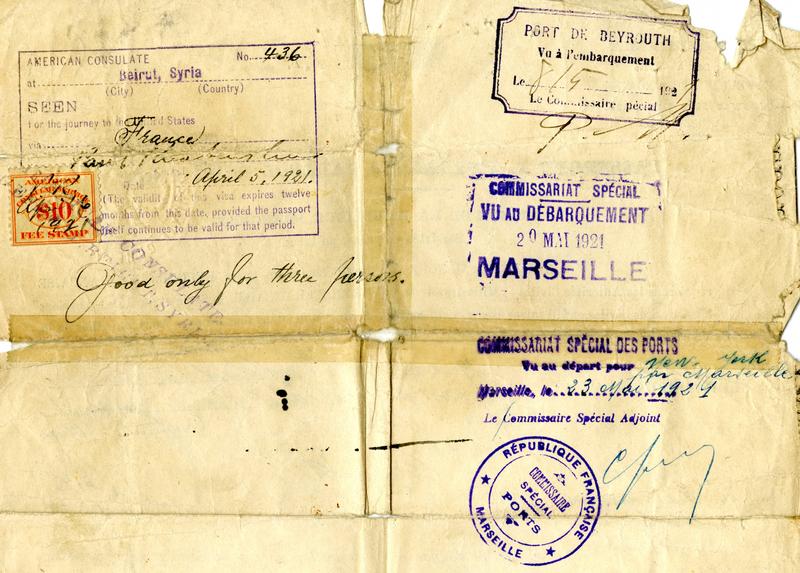

Fig. 5: Passport issued to Mihjé Haddad and her sons Constantine (14) and Michel (9) on 31 March 1921 © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

After intensifying in the early twentieth century, emigration from Mount Lebanon to the USA continued well into the period of the French Mandate, with passports evolving to include photographs as well as verbal descriptions of the traveller’s visible characteristics (Fig. 4). As had been the case since the 1860s, the single greatest advantage enjoyed by would-be migrants from Mount Lebanon – certainly compared to an Armenian family, for example, in Anatolia – was proximity to the way out. Even in the Lebanese hill country, contact with foreign traders, local agents and other intermediaries who could facilitate overseas travel was relatively easy. All a traveller had to do was cross an effectively invisible line between the mutasarrifate and Beirut, since 1864 part of the amalgamated neighbouring province of Syria, and they were at the port, where ticket money was more important than the correct exit documentation.

Fig. 6: Back of Mihjé Haddad's passport (detail), showing her route to America © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

More importantly, even if they could not board at the Port of Beirut – and many thousands certainly did – the internal mürur tezkiresi was sufficient to convey a migrant within the empire to another port of departure. Egypt had been under British military and civilian administration since September 1882 but was still, in Ottoman eyes at least, part of the empire, so Port Said and Alexandria could be reached on a domestic travel permit. The reverse of the Yūsuf Naṣr passport (Fig. 7) is stamped by a Beirut Port Authority official, alongside the scribbled remark ‘Departed for Egypt 11 Teşrinisani 21 [24 November 1905]’. After that, as the Ottoman Foreign Ministry noted with irritation, onward travel to transatlantic transit hubs such as Marseille or Le Havre in France and Liverpool or Southampton in the United Kingdom – and even direct to destination countries like Brazil – only required a basic proof of identification for which a valid mürur tezkiresi would again suffice. Céline Regnard has established beyond doubt that French diplomats and officials in cities such as Marseille actively colluded with French shipping companies, even when they knew that the mutasarrif of Mount Lebanon was actively trying to deter mass emigration, to maximise trade by picking up passengers at night well away from the main Port of Beirut, issuing easy transit visas for the travellers’ short stay in France and, above all, completely ignoring the ‘vexatious’ ban on passport-free travel. So the very autonomy granted to the people of Mount Lebanon as a mutasarrifate in 1861 relaxed the controls that might have held them in place elsewhere in the empire – opening up, as Akram Khater put it, ‘avenues of social and physical movement within and out of the country’.

The Ottoman passport had been conceived and refined as instrument of state control, a tool with which to identify, count, locate, restrict and control its citizens. In the latter areas, it failed dramatically, especially in the context of the mutasarrifate. Successive laws were simply bypassed, if necessary by means of bribery, enabling the determined migrant to use his or her passport as an essential part of their escape kit. Despite that explicit relationship between the passport and Ottoman law enforcement, however, the intrinsic value of the document to the holder, especially for those whom it enabled to make a new life outside the mutasarrifate, is clear, both from the signs of repeated use – the creases, folds, smudges, stains and repaired damage – and from the simple fact that so many have survived among treasured family papers.

Fig.7: Passport issued to Yūsuf Naṣr Muraʾib and endorsed for his one-way journey to Alexandria on 24 November 1905 with his second wife, Warda, and four of his children © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum

Recommended reading:

Abu-Manneh, Butrus. ‘The Province of Syria and the Mutasarrifiyya of Mount Lebanon (1866-1880)’. Turkish Historical Review 4 (2013): 119–34.

Akarlı, Engin Deniz. ‘Ottoman Attitudes Towards Lebanese Emigration, 1885-1910’. In The Lebanese in the World: A Century of Emigration. Eds. Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi. London: Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1992: 109–38.

Akkoç, Alim Baki. ‘Osmanlı Devleti’nde Pasaport Nizamnameleri ve Bunların Uygulamadaki Boyutları’ (‘Passport Regulations in the Ottoman State and Their Dimensions in Application’). MA thesis, Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts, Istanbul, 2019.

Baycar, Muhammet Kazim. ‘Ottoman-Arab Transatlantic Migrations in the Age of Mass Migrations (1870-1914)’. DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 2015.

Ekinci, Mehmet Uğur. ‘Reflections of the First Muslim Immigration to America in Ottoman Documents’. In Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present. Eds. Deniz Balgamiş and Kemal Karpat. Madison, WI: University of Madison Press, 2008: 45–56.

Eryılmaz, Burak. ‘Unearthing the Past: Passport Regulations in the Ottoman Empire’. History Studies 11/6 (2019): 2003–16.

Findley, Carter V. Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte, 1789-1922. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Gutman, David. The Politics of Armenian Migration to North America, 1885-1915: Sojourners, Smugglers and Dubious Citizens. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

– – . ‘Travel Documents, Mobility Control, and the Ottoman State in an Age of Global Migration, 1880–1915’. Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 3/2 (2016): 347–68.

Hanley, Will. ‘What Ottoman Nationality Was and Was Not’. Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 3/2 (2016), 277–98.

Karpat, Kemal. ‘Ottoman Population Records and the Census of 1881/82–1893’. International Journal of Middle East Studies 9/2 (1978): 237–74.

– – . ‘The Ottoman Emigration to America, 1860-1914’. International Journal of Middle East Studies 17/2 (1985): 175–209.

Khater, Akram. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

– – ‘Why Did They Leave? Reasons for Early Lebanese Migration’. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies, 15 November 2017.

– – and Marjorie Stevens. ‘The Early Lebanese in America: A Demographic Portrait, 1880-1930’. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies News, 8 November 2018.

Liberatore, Riccardo. ‘Border Contagion: Transit migration from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic c. 1860-1914’. PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2019.

Pearlman, Wendy. ‘Emigration and Power: A Study of Sects in Lebanon, 1860–2010’. Politics & Society 41/1 (2013): 103–33.

Regnard, Céline. En transit: Les Syriens a Beyrouth, Marseille, Le Havre, New York (1880-1914). Paris: Anamosa, 2022.

Safa, Élie. ‘L’Émigration Libanaise’. PhD thesis, Université Saint-Joseph, Beirut, 1960.

Yılmaz, İlkay. ‘Governing the Armenian Question through Passports in the Late Ottoman Empire (1876–1908)’. Journal of Historical Sociology 32/4 (2019): 388–403.

– – . Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2023.