Purpose

Aims of the project

The late Ottoman period witnessed some extraordinary and lasting breaks with the past. Some were physical migrations, with hundreds of thousands of people relocating from the Middle East to discover and embrace new worlds in North and South America, Europe and Australia. Others travelled to South Asia and West Africa, flitting within and between the imperial domains of the Ottoman Empire, France and the United Kingdom. Small-scale traders, intellectuals seeking new horizons, embattled minorities: many of them setting out to reinvent themselves and discard inherited world views. Some of the most profound changes were internal, as Middle Eastern societies experienced an often turbulent evolution of both personal and collective identities, in religion, political thought, artistic expression and philosophy. For a remarkable period between 1860 and 1930, individuals from Cairo and Damascus to Smyrna and Beirut – as well as those in a global diaspora that spread from Marseille to Calgary and Boston to Buenos Aires – were faced with opportunities and challenges that resulted in true generational change, in both self-perception and the perception of outsiders.

Relationships between and among the region’s religious groups were a key part of this complex picture, as evolving forms of sectarian identity – encompassing issues of religion, community, law and politics – became both a powerful force in the volatile history of a decolonising Middle East and an important factor in community development in the New World context. For some, violence was, during this fin-de-siècle period, a powerful force: experienced through episodes of widespread killing and displacement, and leading to the establishment of sizeable Eastern Christian communities across America. But for others, new forms of belonging offered the foundation stones of new relationships between Maronites and Orthodox Christians in the tenements of Lower Manhattan or Muslims and Christians in the neighbourhoods of Sao Paulo.

This generational mobility did not happen in a vacuum: it took place within the purview of an imperial power that, while fading, still had reach: to manage that mobility by withholding or granting travel documentation and to maintain some oversight over émigrés by placing consular representatives at the heart of overseas communities. Within the Ottoman Empire, too, migration occurred: a migration of status – as minorities pinned in place by old labels achieved social and political equality, their identities and rights formally validated and the perception of their communities reformed – and a movement away from a presumption of state authority over sectarian and community inter-relationships.

As new identities were formed, the results of these generational shifts were far-reaching. In the new worlds of the diaspora, the post-migration generation was focused for the large part on assimilation rather than return. Early battles with racism and sectarian prejudices articulated scarcely more subtly by host communities were rapidly forgotten as Syrians, Turks and Arabs became, simply, Canadian, French and Brazilians. Education played a key part, accelerating the desuetude of the Arabic language, active religious practice and many of the cultural norms that suddenly seemed to belong in another place, another time.

Within this context, the Moving Stories project concentrates on two areas of research. First, the project will explore the global circulation of Middle Eastern sectarianism and the variety of sectarianisms that developed in specific localities across the Middle East, the Americas, and Europe. Second, the project will focus on what it calls the ‘moving stories’, or emotive forms of storytelling, used by individuals to describe, explain, and represent sectarianism as much to themselves as to multiple publics in local, national, and international contexts.

The project, based at the Faculty of History at the University of Oxford, is led by Professor John-Paul Ghobrial and runs until 30th September 2026.

For further details, please get in touch via our Contact page.

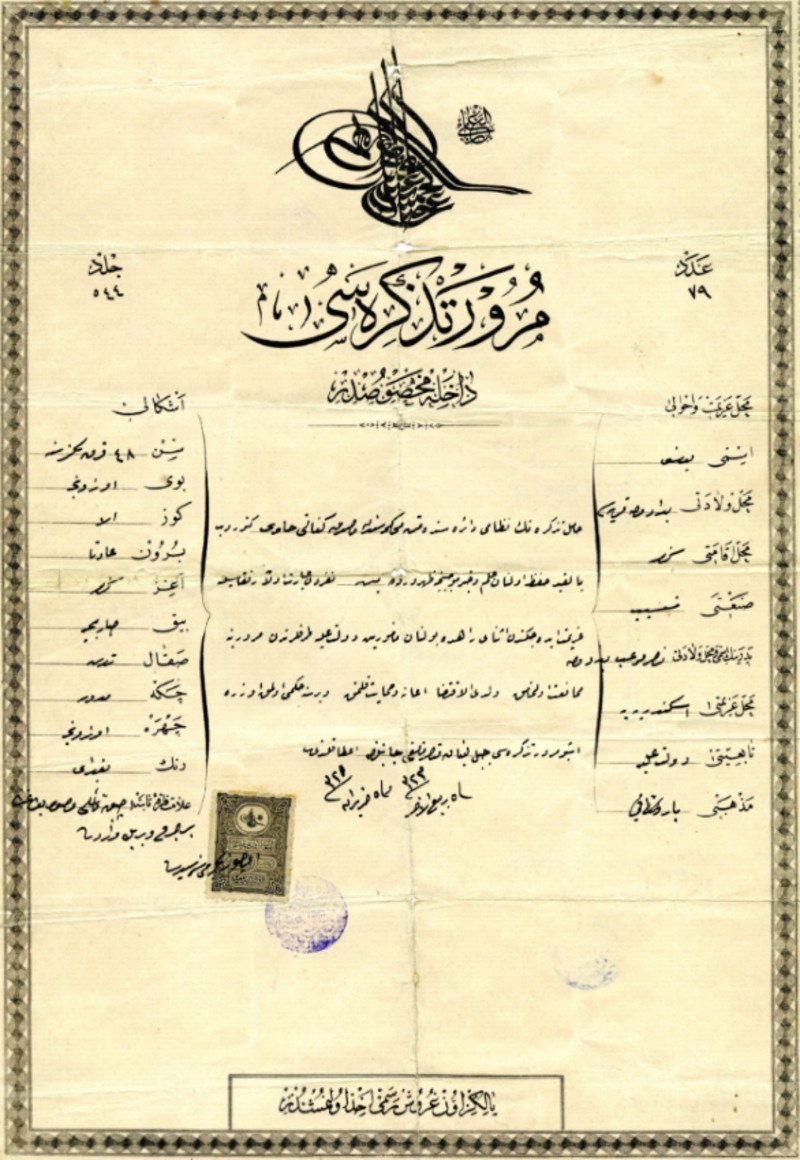

Fig.7: Passport issued to Yūsuf Naṣr Muraʾib and endorsed for his one-way journey to Alexandria on 24 November 1905 with his second wife, Warda, and four of his children © Joseph Nusser Family Collection, Arab American National Museum