Iraqi archives: A history of fragmentation and restitution

Entrance to the Iraqi National Library and Archive, Baghdad © Chris Cooper-Davies 2023

The haze of the 2003 Iraq war and its immediate aftermath make it difficult to know exactly what caused the destruction of 60% of the documents held at the Iraqi National Archive and Library (INAL), 25% of its books and 95% of its rare books. White phosphorus munitions dropped by the coalition forces may have played some role, as well as two nights of looting and arson in April 2003. When historian and activist Saad Eskander arrived to take on his role as the first director of the INLA in post-Baʿathist Iraq, he found the building in near ruins, a charred reminder of the wholescale destruction of the Iraqi state. Undeterred, Eskander spent the following five years rebuilding the archive from scratch, documenting some of these efforts in a blog which offers harrowing insights into life in Baghdad during the sectarian civil war of 2006 to 2008.

While Eskander faced the daily challenges of archival management in the midst of car bombings, street fighting and the kidnapping and murder of several staff members, he was able to appreciate the importance of safeguarding Iraq’s archival heritage for future generations. Unlike the old Baʿathist-run archive, the new INLA would be for all the Iraqi people. The austere statue of Saddam at its entrance – which somehow managed to survive the arson attacks of April 2003 – was replaced by the poet laureate of Iraq: the eternally cheeky, confessionally ambiguous but universally adored Abbasid bard, al-Mutanabbi. Meanwhile, Eskander became a campaigner for the restitution of the millions of files pertaining to the secret intelligence services of the outgoing Ba’athist regime, which had been removed from Iraq in the wake of the US invasion. For Eskander, this was a matter of principle: ‘as they [the files] are public property; they belong to the country and its society.’ This belief led him to engage in a conflictual discourse with Kanan Makiya, the Iraqi academic and proponent of the US invasion who had instigated the files’ removal to America in 2005.

The controversial saga of the elusive Baʿath Party Archive captured the imagination of journalists and academics alike. But it begs a broader question about the location and accessibility of the archives of modern Iraq which pre-dates 2003.

Historians working across the Middle East are engaged in historical and critical studies of archival formation and fragmentation. Iraq’s modern history has been defined by waves of violent and non-violent battles for sovereignty, authority, jurisdiction and influence: that is, the very right or prerogative to constitute the Iraqi archive. The multiple repositories of documents, correspondence, manuscripts and audio-visual materials which form the analytical sustenance of a national history, and are usually located in a single building or at least a single city, are scattered in multiple cities and repositories. Some have been lost entirely. The future of Iraqi history and historiography, if not nation-building itself, is contingent on an ongoing process of archival restitution.

The records of Iraq are one of the most continuous moving stories of the nineteenth and twentieth century Middle East. When Britain invaded and occupied Ottoman Iraq in 1915, they cut it off from the administrative and archival apparatus of the Ottoman Empire. While the Iraqi state soon developed its own archival infrastructure, the most significant papers pertaining to the British Mandate in Iraq were mostly wired to White Hall, and are now preserved in the voluminous colonial office files at the British National Archive. Some are can also be found in New Delhi. The INLA was established in the 1920s, and expanded throughout the mid-twentieth century. Yet along with a great many other Iraqi libraries and private collections, it was underfunded and undermined by the rise of Saddam Hussein’s authoritarian regime and the years of war with Iran and the United States that followed. As the Iraqi diaspora in Europe, America and Iran ballooned from the 1980s, family papers and demi-official archives migrated across nations and continents. Today, writing on Iraq can be just as fruitful in London or Detroit, as in Baghdad or Basra.

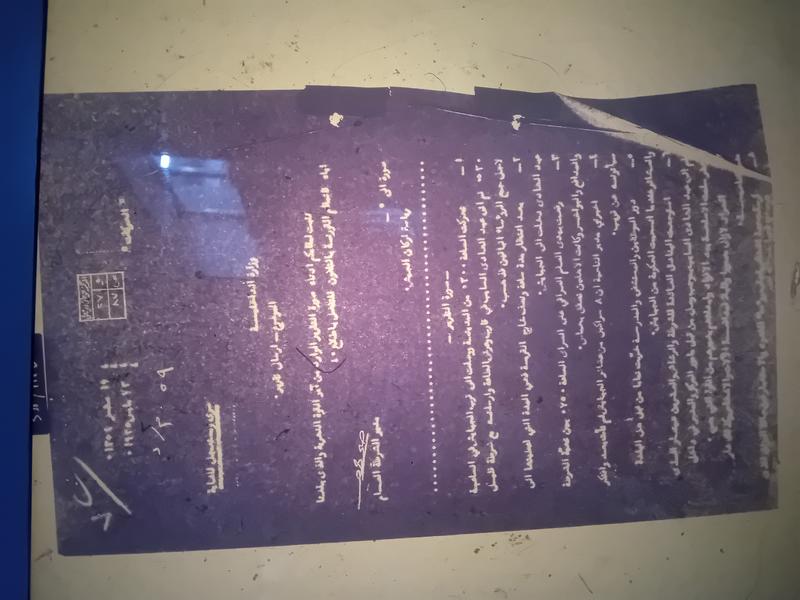

The fate of the Iraqi archive and, with it, the potentialities of Iraqi history writing, were dealt an ambivalent hand by the toppling of the Baʿathist regime in 2003. On the one hand, the end of Baʿathist totalitarianism and the liberalisation (albeit still fragile) of the Iraqi public sphere enabled new projects of archival accumulation, promotion and publication. Yet on the other, the occupation, security disintegration and the subsequent drift into civil war directly or indirectly led to the displacement, decimation or damage of millions of documents and books. Visiting the INLA for my own research in September 2023, it was not only a challenge to work through countless missing files, but also to decipher meaning through the layers of water and fire damage adorning many documents.

A damaged file from the INLA about the 1935 tribal insurrection on the Euphrates

The post-2003 removal of archival collections from Iraq is without doubt the most controversial archival scandal of modern times. It has been variously described as plunder, illegal under various regulations of international law, and, according to the Iraqi legal scholar Husam Khalaf, ‘cultural genocide.’ Three types of records were taken out of Iraq: the first was a very substantial portion of the official documents of the Iraqi government, which coalition forces transferred to Doha for intelligence purposes. The second, after being discovered in the waterlogged basement of the Iraqi Intelligence Headquarters in Baghdad, was the Iraqi Jewish archive, a vast collection of books and documents belonging to the Iraqi Jewish community. The third was the Baʿath Party Archive, which the Iraqi Memory Foundation, an NGO and US Defence Department Contractor, airlifted out of Baghdad with the assistance of the US State Department in 2005. All of these incidents represent unresolved legal and diplomatic disputes between Iraq and the United State. The last continues to attract the most academic and media attention because the Baʿath Party Archive contains millions of documents relating to the security and intelligence apparatus of Saddam’s regime. The Iraqi Jewish archive and the Baʿath Party archive are available to researchers in the US, but access is limited and often impossible for Iraqi-based scholars themselves.

Archives are important institutions for engendering community cohesion and restorative justice. But they can equally be repositories of dark histories of conflict and betrayal. They contain uncomfortable secrets, the names and identities of informants, and they can reopen forgotten feuds and undermine established narratives of historical events. All these considerations shaped Makiya’s approach to the Baʿath Party Archive, which he discovered by chance underneath the Mausoleum of Michel Aflaq in Baghdad. Makiya, who set up the Iraqi Memory Foundation in 1992, had initially aspired to create an archive of the old regime which would serve as a focal point for national reconciliation. In this he was partially influenced by the East German experience, where the Stasi archives continue to be an important institution for legal and psychological reckoning with the crimes of the East German state.

Perhaps in light of the fast deteriorating security situation in Iraq in the years following the American occupation, Makiya put his proposals to build an institution of national reconciliation on ice. He decided that, unlike East Germany, Iraqis were ‘just not ready’ for the contents of the Baʿathist security files. While Eskander and a cacophony of voices in America and Iraq strongly denounced this view, Makiya was able to put all the documents in his possession in the custodianship of the Hoover Institute at Stanford University. While the original files were returned to Iraq in 2020, their current whereabouts are unknown. Anxieties remain about the possible ramifications which could follow their public release.

The search for a national reckoning with the past cannot be solved through the restitution of state archives alone. In Iraq, history and collective memory are central to ongoing struggles about Iraqi national identity, culture and geo-politics. Past Iraqi states, in their colonial and authoritarian manifestations, have only ever been able to reflect hegemonic narratives. Part of the process of archival restitution in Iraq necessarily means the inclusion of sources which give voice to marginalised political, social and religious actors who fell through the cracks or into the traps of the state’s bureaucratic machinery: the working classes, the rural masses, the political oppositions, and the many thousands of migrants and returnees.

Archival historians of Iraq – especially those working in the Euro-American academy – have not always been immune to the biases of Iraq’s state archives. This sets them apart from Iraqi historians themselves, who have often relied less on official archival holdings than their European-based peers. Historians such as Abd al-Razzaq al-Hasani, Ali al-Wardi and Abbas al-Azzawi drew on their own personal and professional networks and, we can assume, substantial personal collections of documents, newspapers, journals and correspondence. It was not uncommon for al-Hasani, for example, to farm out the answers to key historical questions to his influential friends, incorporating into his work their personal opinions on matters as important as the reasons for the Iraqi revolution of 1920 or the history of the Iraqi political parties.

This partly reflects a structural power imbalance which debars easy access to colonial sources for Iraqi historians of Iraq. It is telling, for example, that the British historian Philip Ireland somehow managed to gain access to British colonial sources for his 1937 book Iraq: A Study of Political Development, well before such files were declassified in the 1970s. Yet the reliance on a different, more personal archival nexus among Iraqi scholars speaks also to their divergent priorities, rooted less in the history of state institutions but in the historical perspectives and aspirations of the Iraqi people. Such a priority continues to this day.

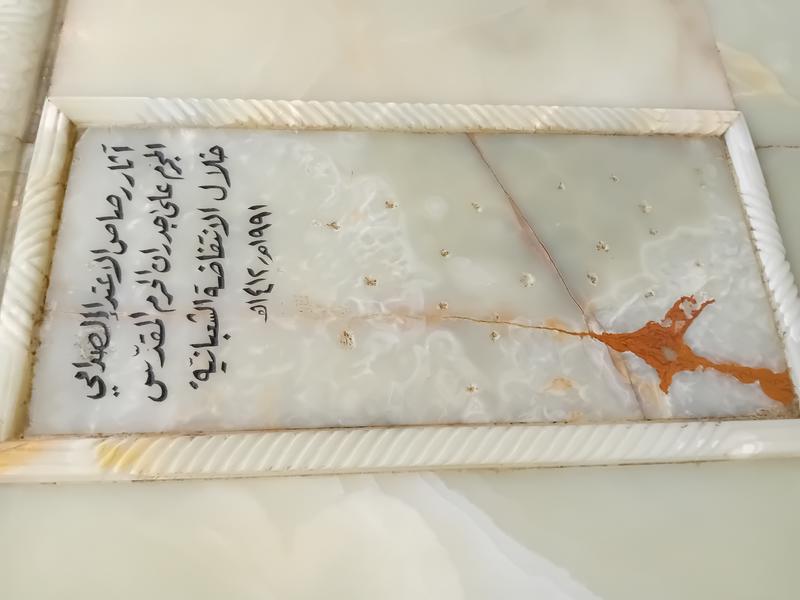

It is this aspiration which has driven a renewed drive to rehabilitate the Iraqi archive in the post-Saddam era. Such a process is especially prominent among those elements of the population who were marginalised or persecuted by the Baʿathist regime. The southern religious centres of Najaf and Karbala are a case in point. When Ba’athist troops attacked both cities following the Intifada against the regime in 1991, they not only murdered indiscriminately and fired upon the shrine of Imam Husayn. They set libraries and manuscript collections ablaze, shot through books and looted manuscripts.

One of the scores of panels in the Shrine of Imam Husayn commemorating the 1991 Intifada

The cultural trauma of this episode forms the context for a concerted drive towards archival preservation and restitution in these religious centres. In Najaf, the new library of the shrine of Imam Ali has republished almost all the journals and newspapers released in the city since the beginning of the twentieth century and made them, along with hosts of other materials, available to the public. Clerical families have amassed collections of documents and manuscripts, opening archives and libraries alongside their seminaries and majalis.

Other minority communities both inside and outside of Iraq have embarked on similar projects. In 2017, the Chaldean Community in Michigan established the first museum dedicated to documenting Chaldean history and culture in Iraq and the diaspora. The Museum’s five galleries amass historical and contemporary artefacts, many of which were donated by the Chaldean community themselves. Their mission is to ‘take visitors from the court of Nebuchadnessar to an immigrant grocery store in Detroit and beyond.’

The new initiatives are outreach programmes as much as they are archival projects, serving up historical documents and images to a growing and interested public via Telegram, Instagram and YouTube. But they are also concerned with the physical restitution of documents, books and manuscripts which should, by rights, be theirs. In some cases, this is a matter of negotiation. The Bahr al-Ulum Centre in Najaf, for example, was obliged to negotiate with the INLA for the return of manuscripts taken during 1991. But in other cases, the obstacles in the way of restitution are structural. Shaykh Muhammad Karbasi is the founder of the Markaz al-Najaf li-Ta’lif wa-l-Tawthiq wa-l-Nashr (The Najaf Centre for Composition, Documentation and Publication), a local history initiative dedicated to the collection and preservation of documents, photographs and manuscripts. He informed me that he had managed to amass copies of almost all the documents pertaining to Najaf from the Iraqi and Iranian archives, but not the British National Archive. It was simply impractical for him or his colleagues to travel to the UK.

The very active Instagram and Telegram pages of the Markaz al-Najaf post daily documents and photographs about the history of Najaf and Karbala

The displacement of the Iraqi archive is an enduring obstacle in the face of a new and energetic Iraqi archival and historiographical renaissance. While the return and unearthing of the Baʿath Party Archive will be an important step in this direction, there is also a need to think about innovative ways to tackle barriers of access to all of Iraq’s scattered and decentralised archival institutions. This is as important for scholars working outside Iraq as it is for Iraqi scholars themselves because the scholarly potential of a more cohesive and interconnected archival landscape – both between Iraqi institutions and between these institutions and Iraq’s various global archival outposts – will facilitate new approaches and interpretations for the country’s contested modern history.

Historians of the Middle East are tackling the problem of archival composition on a number of fronts, as they strive to incorporate methodologies which capture experiences and modes of thought above and beyond those of the state. In this, national historians can take inspiration from work in the discipline of global history, which has for a long time sought to grapple with disparate and disconnected archival regimes in its quest to tell moving stories of migration, connection and global exchange. The biases of any one Iraqi archive can only be ameliorated if the Iraqi archive is allowed to emerge, as a visible and accessible institutional nexus. Inevitably, such a discovery will involve looking beyond the borders of Iraq itself, not only to London and Istanbul, but equally to Cairo, Detroit and Tehran. These are just some of the destinations where Iraqis have moved to and between throughout the twentieth century, sometimes as refugees but also as students, entrepreneurs and tourists. A final caveat to this blog is that the process of Iraq’s archival restitution does not prioritise the national and local at the expense of the global.