From Ancient Grudge to New Mutiny: Communal Conflict in Early Twentieth-Century Syrian Massachusetts

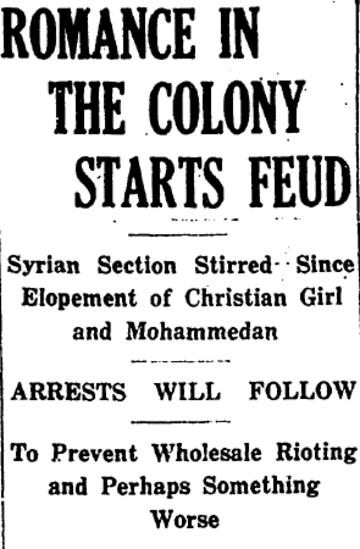

Springfield Daily News, 13 Sept 1916

In the venerable tradition of American-immigrant Shakespeare adaptations, allow me to propose another setting for the story of Romeo and Juliet: downtown Springfield, Massachusetts, early twentieth century, a community of Arabic-speaking immigrants. There, in 1916, Allie Soffan and Elizabeth Moffett ran away to marry against the will of Elizabeth’s family. Both “Syrians” in local parlance, Soffan was Muslim and Moffett was Christian. Their elopement, according to the Springfield Daily News, sparked a scuffle between local Muslim and Christian Syrians, leading to arrests of several Christians and a special police detail for the Syrian neighbourhood.[1]

The Daily News article puts us firmly in the symbolic territory of Montagues and Capulets. It notes that there had been “several fights in the [previous] two years” because of Soffan and Moffett “keeping company,” labelling the subsequent confrontation a “religious war” between “adherents of the two factions.” Indeed, the young couple’s escape punctuated a little-studied decade of communal violence in Springfield. Yet the article also hinted that, in addition to religious factionalism, “trade rivalry by peddlers and merchants” had heightened tensions.

In a pioneering study on the Arabic-speaking community of Springfield, Naseer Aruri treats these communal tensions as ephemeral: “these incidents were not related per se to religious antagonism, but when a crisis erupted over business deals or communal gossip, religious solidarity was manifest in the formation of factions.”[2] Aruri rightly questions the Daily News’s notion of a “religious war.” Yet his reference to petty disputes “over business deals or communal gossip” begs the question: why did some such quarrels arouse “religious solidarity,” while others presumably did not? And what is “religious solidarity,” if not a latent “religious antagonism”?

Without a clear sense of how economic interests and communal identities overlapped, we are left with an image of “trade rivalry” as the flimsy pretext for outbursts of underlying hatreds.[3] Springfield’s “ancient grudge,” however, was far from ancient. A preliminary analysis of the drama surrounding Soffan and Moffet’s elopement shows that migrant socioeconomic conditions shaped emerging senses of communal belonging, and vice versa. Conflict between Christian and Muslim Syrians in Springfield was not an inevitable clash, but the confrontation of two crystallizing social and communal formations.

One aspect of identity that often coincided with religion in Syrian Springfield was hometown origin. The Christians came largely from north Mt. Lebanon, particularly coastal Tripoli and mountain villages like Zgharta, Ehden, Basloukit, and Rachiine.[4] Thomas Ysbeck (Yazbek), who was arrested in the confrontation following the elopement, was born in Tripoli.[5] The Muslims, including Allie Soffan himself, hailed mostly from a western Biqa’ valley village called Mdoukha.

The brush-up that followed the elopement, then, was specifically between Christians from the north and Muslims from the Biqa’. The former were Maronite Catholics, members of an autonomous church dominant in their mountainous home region. Migrants from the Biqa, on the other hand, were Sunni Muslims from an agricultural plain between the urban centres of Beirut and Damascus. Geographically distant, these two groups probably lacked any ties with one another beyond their shared Arabic language and Ottoman subjecthood. In contrast, Muslim Syrians in Springfield may have had connections with local Greek Orthodox Christian migrants from the village of Aitha al-Foukhar, immediately to the north of Mdoukha.[6] It does not appear that this third group was involved in the tensions around the elopement.

Contemporary Lebanon

Hometown links were important to the transatlantic journeys and livelihoods of Syrian immigrants in the Americas. Often, established wholesalers facilitated the immigration of fellow townsmen and provided initial batches of consumer goods for them to peddle. In Springfield, the dry goods salesman Peter Karam would be remembered as “like an uncle or a father” to fellow migrants from north Lebanon.[7] He signed as a witness to the naturalization declaration of John Moffett of “Banni” (presumably Bane, near Ehden), likely a kinsman of young Elizabeth’s.[8] In parallel fashion, the witnesses for the declaration of “Mohammed Soffen,” presumably a relative of Allie’s, included dry goods salesman Ahmad Ali of Mdoukha and silk dealer George Makol of Aitha al-Foukhar.[9]

Sponsorship through hometown social networks offered the promise of financial success to newcomers. Yet the path from peddler to wholesaler, while common enough, was far from linear. One of the named members of the Christian group suspected of violence after the elopement in 1916, Joseph Obessey [Yusuf al-Qubrusi], is listed in local sources alternately as a labourer and a peddler.[10] Many Syrian immigrants similarly flitted between petty commerce and manual labour.

Patron-client relationships also offered a platform for wealthier migrants to become communal representatives. In Springfield, Peter Karam’s business partner Peter Franjia and his wife Mantura mediated between migrants and city officials and police.[11] Such figures also fuelled the Syrian diaspora’s associational life, which often took on a sectarian hue. It was presumably migrants from Zgharta and its environs who founded Springfield’s Yousef Bey Karam Society, named after the northern Lebanese Maronite popular hero.[12] With Maronites sharing worship facilities with the Irish Catholic population, then in the midst of a long struggle with local Protestant elites, the vision of Mt. Lebanon as a refuge of Maronite Catholicism implicit in Yousef Bey Karam’s hagiography may have found renewed purchase in this context.[13]

Muslim collective life also flourished. The Springfield Republican detailed the celebration of Ramadan in 1917 by around one hundred Muslim Syrians, who gathered at the “store of Niss & Soffan.”[14] The former was Hassan Niss (Husayn Mohammad al-Niss) of Mdoukha, a wholesaler, interpreter, and president of the “Muslim Youth Society” in Springfield.[15] Like his counterparts, then, Niss likely spearheaded efforts relating to faith and community among Muslim migrants.

Main St, Springfield (1908)

The stage is now set to return to our star-crossed lovers. Having long endured the “strong opposition on the part of the parents of the girl and by others in the Christian colony of Syrians,” the couple had fled to nearby Brattleboro, Vermont, where they married. After some weeks, a “disturbance” broke out at Niss’s shop:

"Now with Sofan gone, the anger of the Christians has turned against Hassan Niss, leader of the Mohammedan faction… He was recently attacked by three or four men and as a result the police have been obliged to send a guard to escort him to and from his home each night. Last night a crowd of 10 or 12 Syrians went to his store and threatened him, but Niss was protected by a crowd of his friends. A large crowd gathered and the Christians scattered when the police arrived."

On the one side of this encounter was Niss, a recognized Muslim “leader” and fellow townsman and business partner of Allie’s. On the other were Maronites from northern Mt. Lebanon that joined the Moffetts in rejecting Allie’s courtship of Elizabeth, including Ysbeck and Obessey, two of the three assailants named in the Daily News article. The elopement had sparked a chain reaction beginning presumably with the discontent of Elizabeth’s parents and culminating in a confrontation of communities at Niss’s shop.

The specific motivations of the individuals who clashed at Niss’s shop are obscured by the passage of time. Yet there is little doubt that both communal and socioeconomic considerations played a role. In fact, there was little to distinguish the two, as each constituted the other. The diasporic environment, and more specifically Springfield, brought about an evolving politics of religious identity layered onto a web of economic, social, and cultural concerns. This was no hidden wellspring of antipathy incited by the violation of old taboos, but a mutable repertoire of affinities and aspirations. Carefully reconstructing this story through local sources shows that conflict in Springfield was the product of communal boundaries in formation. Elizabeth and Allie did not so much breach an “ancient grudge” as evade a host of novel ones.

There is a final sense in which the couple’s fate deviates from their Shakespearean counterparts. The Daily News reported that they had escaped “to a large western city” in 1916, with marital life in Springfield an apparent impossibility. Yet the 1920 census finds Allie and Elizabeth together there again, with two children and three lodgers, one of whom was Niss. If a census entry is not exactly a happy ending, it is also no story of woe – a reminder, perhaps, that communal difference is constantly made and un-made.

[1] “Romance in Colony Starts Feud,” Springfield Daily News, 13 September 1916.

[2] Naseer Aruri, “The Arab-American Community of Springfield, Massachusetts,” in Arab Americans: NK09 (New Haven: Human Relations Area Files, 1999), 51-2. See also, Ibrahim Othman, Arabs in the United States: A Study of an Arab-American Community (Amman: Published with the help of the University of Jordan, 1974), 52.

[3] Ussama Makdisi, “Corrupting the Sublime Sultanate: The Revolt of Tanyus Shahin in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 42/1 (2000), 181.

[4] S.A. Mokarzel and H.F. Otash, The Syrian Business Directory (New York: al-Huda Press, 1908), 134-5.

[5] “Thomas Abraham Yasbek,” U.S. World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942.

[6] Nagib Abdou, Abdou’s International Commercial Directory, Especially of the Arab Speaking People of the World (1910), 71.

[7] Othman, 34.

[8] “John Moffet,” Petition for Naturalization No. 2862A, Police Court, Hampden County, Vol. Jan 19, 1898 – Mar 31, 1906.

[9] “Mohamed Soffen,” Petition for Naturalization No. 217, Superior Court of Hampden County, Massachusetts.

[10] U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 1920 United States Federal Census, Hampden County, Springfield, Ward 2, District No. 105; Springfield Directory (Springfield, MA: Price & Lee Co.,1921), 651; Springfield Directory (Springfield, MA: Price & Lee Co.,1921), 611.

[11] Othman, 39.

[12] Ibid., 70.

[13] Rhys H. Williams and Nicholas Jay Demerath, A Bridging of Faiths: Religion and Politics in a New England City (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 3-21.

[14] “War after Elopement,” Springfield Daily Republican, 14 September 1916.

[15] “Tilighrāfāt lā silkīyya,” al-Sāʾih, 22 May 1916.