Communal Conflict and the Early Syrian-American Experience

Josh Grundy-Tenn is a second-year Ancient History and History student at the University of Nottingham, originally from North-East London. He has a particular interest in the Middle East and intends to pursue his dissertation on a related topic.

Josh has previously volunteered at the University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections department, where he catalogued some of the correspondence of Lord William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, who served as the first Governor-General of India in 1834. This experience strengthened his resolve to pursue postgraduate studies in global history. Taking part in the UNIQ+ research internship supervised by Prof John-Paul Ghobrial, Josh looks forward to working with the Moving Stories team and contributing to such an incredible project.

For more information about the UNIQ+ Moving Stories internships, read the Faculty’s report.

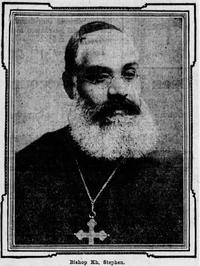

On 31 January 1906, John Stephen, brother of Maronite Bishop Khairallah Stephen, was murdered in a Syrian restaurant following a shootout. The convicted murderers, George and Elias Zraik, were followers of Greek Orthodox Bishop Raphael Hawaweeny and had initially set out to find the controversial editor of the newspaper al-Hoda, Naoum Mokarzel. The murder was a result of the sectarian tensions present in New York at the time. This incident encapsulates the sectarianism within the Syrian communities in New York during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the city, religious divides could be inflamed by disputes between prominent Syrian figures, often involving newspapers. The term 'Syrian' during this period (1880-1920) referred to the people of the Ottoman province of Syria, which encompassed modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. Here, following contemporary usage, 'Syrian' will refer to people from all these regions, and 'Syrian colony' to a community of Syrian immigrants in a particular place. The role of Syrian newspapers, which had specific religious and political affiliations and frequently traded insults and critiques, is a distinctive aspect of the 1906 incident in the context of the early Syrian-American experience.

As seen in the murder of John Stephen, communal conflict often formed along confessional lines. Most of the Syrians who came to America during this time were Christians divided between Greek Orthodox, Maronite, Melkite, and Protestant churches; only a small minority was Muslim. There were some clashes between Syrian Christians and Muslims during this period in the United States. For example, the Sioux City Journal in 1913 reported that the assault and robbery of a Christian merchant, Mokolle Andrews, was the result of an ongoing feud between Christian and Muslim Syrians in the city.[1] Generally, however, more opportunity for communal conflict existed between the different Christian sects.

Simultaneously, much of the communal conflict in the Syrian communities across America was sparked by personal feuds and crime. For instance, in the Syrian colony of Omaha, conflict between two Syrian men over a woman over the course of a week rapidly escalated into a brawl in the street which involved up to twenty Syrians and ended with the murder of Najeeb Saidy, a shopkeeper that was reportedly trying to stop the violence. Additionally, Joseph and Solomon Hassan were arrested and sentenced over the murder of their cousin Fred Nawfl, a Syrian peddler. It was noted that when Nawfl’s body was discovered merchandise and cash that he was known to have had was missing, indicating a monetary element to the murder.[2]

Additionally, racism and xenophobia were common in the migrant experience for those who did not fit American ideals of race and religion. Like other groups that came to the United States, Syrians dealt with the wide range of difficulties inherent in uprooting their lives, moving to a foreign land, forming new bonds and communities, and navigating American prejudices. These difficulties significantly affected daily life for Syrians. For example, it was reported that the Syrian colony of Omaha, Nebraska, was attacked by a mob of three hundred on 15 July 1901, forcing the community to defend themselves with the help of a single police officer. The Omaha Daily Bee, which reported the incident, noted the mob’s intent of ‘wiping them Arabs off the face of the earth,’ and it seemed this violent event prompted the colony to relocate to a safer part of the city.[3] This is one of the most salient examples of xenophobic and racist violence towards Syrians during this period.

The murder of John Stephen illuminates a distinctive element of conflict in the early Syrian-American experience. This incident is notable as it involved the murder of the brother of a prominent religious figure. The involvement of both the followers of Hawaweeny and Stephen, highlights the communal aspect of conflict among Syrians. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle on 4 February, 1906, reported the tensions between the different communities and the severity of the situation in New York. It was reported that “apparently all that was needed was a signal and the followers of the two churches would have been plunged into a bloody battle in the name of their god and religion. Between 10,000 and 15,000 Syrians feel the threat of danger in the air.”[4] This report was written only a month after the murder of John Stephen. It is important to note that this report was from the perspective of a non-Syrian who may not have fully understood the situation. An American observer would also likely have had a prejudiced view of Syrians, as those from the East were often regarded as violent and 'fanatical' in their religious identity. However, it still conveys the significance of these tensions and the major impact they had on the Syrian communities.

The Syrian communities of New York were generally seen as quite peaceful prior to 1905. In the preceding years, there was notable cordiality, and in 1904 both the Maronite and Greek Orthodox Syrians were united in their Christian support for the Russians in the Russo- Japanese war. Additionally, Mokarzel congratulated Hawaweeny on his appointment as the Bishop of the Syrian Greek Orthodox Church in North America. However, Hawaweeny’s growing influence became a point of contention among the Syrian elite of New York, while Syrian newspapers were increasingly paid and used by businessmen and key figures to print slanderous articles about political and business rivals.[5] It was within this context that friction between the Maronite and Greek Orthodox communities increased. A major incident that followed this shift was a ‘pistol battle’ outside the home of Mokarzel on September 19, 1905, which saw Hawaweeny and several of his parishioners arrested. The police argued that Hawaweeny “led a number of his followers in an armed attack upon the home [of Mokarzel].”[6] However, the Bishop argued that this was not the case and that he was under constant threat of assassination. Because of this, whenever he left his home at night, he was always accompanied by several of his followers, and he had been going to visit a sick friend when the shooting began. Hawaweeny said about the incident, “I am convinced it was a feigned pistol duel, with the purpose of murdering me by hitting me with what would appear to be a stray bullet.” Regardless of which version of the story is true, the potentially planned attack on the home of Mokarzel and the threat of assassination to Hawaweeny demonstrate the dire condition of relations between the New York Syrian communities, and how violent, public, and pervasive this conflict could be. This episode was significantly influenced by the Syrian newspapers in New York, which often had religious affiliations. For instance, al-Hoda (The Guidance) tended to follow the Maronite community, while Kawkab America (Planet America) and Mirat al-Gharb (Mirror of the West) tended towards the Greek Orthodox community. Naoum Mokarzel established al-Hoda, the longest-running Syrian newspaper, which printed its first edition in 1898. Mokarzel was a contentious and influential figure that used his platform to voice insults and to critique those that he disagreed with. Communal conflict was often exacerbated by political and personal discord promoted through the press this way. This can be seen in the death of John Stephen. According to newspaper reports, followers of Hawaweeny had come over from Brooklyn to wreck the offices of al-Hoda, which had printed some bitter things about Hawaweeny. Unfortunately, these insults are left out of the New York City English-language newspapers that reported the incident. In search of Mokarzel, the supporters of Hawaweeny, headed by George and Elias Zraik, went to the restaurant where he usually dined and there the fight began in which John Stephen was murdered.[7]

In conclusion, internal conflict between different religious communities played an occasional, but significant role in the early Syrian-American experience. Tensions between different religious groups within the Syrian community often led to violent incidents, such as the murder of John Stephen and the gun fight outside the home of Mokarzel. The role of Arabic newspapers, often aligned with specific religious sects, further complicated the dynamics within the Syrian community, amplifying tensions and fuelling disputes. However, not all conflicts were rooted in sectarianism. Personal disputes and criminal activities also played a significant role in the daily lives of Syrian migrants, mirroring the experiences of other immigrant groups during this period. Additionally, Syrians faced significant external challenges, including racism and xenophobia, which repeatedly resulted in violence. Ultimately, the early Syrian-American experience was multifaceted, shaped by both the struggles of integration and the internal divisions that mirrored the complex social and religious landscape of their homeland.

[1] “Battle over religion,” The Sioux City Journal, 12 August 1913.

[2] “His race is one of dreamers as to truth,” Omaha World-Herald, 4 December 1901; and “Blow not aimed at Saidy,” Omaha Daily Bee, 4 December 1901.

[3] “Thirteenth Street Strife,” Omaha Daily Bee, 15 July 1901.

[4] “Bitter Syrian feuds caused by church war,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 February 1906.

[5] Manal Kabbani, “The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905” (The College of William and Mary: Williamsburg, Virginia, 2016), 68-72.

[6] “Assassins are after him, says Bishop in riot,” The World, 19 September 1905.

[7] “Held for Syrian murder,” The Sun, 10 March 1906.

References

Primary Sources

“Thirteenth Street Strife,” Omaha Daily Bee, 15 July 1901.

“His race is one of dreamers as to truth,” Omaha World-Herald, 4 December 1901.

“Blow not aimed at Saidy,” Omaha Daily Bee, 4 December 1901.

“Assassins are after him, says Bishop in riot,” The World, 19 September 1905.

“Bitter Syrian feuds caused by church war,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 February 4

1906.

“Held for Syrian murder,” The Sun, 10 March 1906.

“Battle over religion,” The Sioux City Journal, 12 August 1913.

Secondary Sources

Manal Kabbani, “The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in

Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905” (The College of William and Mary: Williamsburg,

Virginia, 2016).

Further Reading

Reem Bailony, ‘Donating in the Name of the Nation: Charity, Sectarianism, and the

Mahjar’, in Practicing Sectarianism, ed. Lara Deeb, Tsolin Nalbantian, and Nadya Sbaiti

(Stanford University Press, 2022), 81–97.

Reyhan Durmaz, ‘Religion, Race, and Letterpress: Orthodox Christians in Nineteenth-

Century New York City through the Lens of Kawkab America’, Journal of the American

Academy of Religion, 91 (4): 854–74.

Steven Hyland, ‘Arabic-speaking Immigrants Before the Courts in Tucumán, Argentina,

1910–1940’, Journal of Women’s History 28, no. 4 (2016): 41–64.

Akram Khater, ‘“Like a Wolf Who Fell upon Sheep”: Arab Diaspora and Religion in

America, 1880–1930’, Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 21, no. 1 (March

2021): 1–26